By James E. Spiotto

The U.S. Supreme Court and virtually all state courts have recognized what the Rhode Island Supreme Court recently reaffirmed: insurmountable, unaffordable government contractual obligations for public pensions must be capable of reasonable and necessary modifications to prevent the financial demise of government, the corresponding failure of public pension systems and the loss of public workers’ employment. A few state courts, most notably in Illinois, have ruled that there can be absolutely no modification, impairment or diminishment of public pension obligations, no matter how little or necessary for the financial survival of government. The fatal flaw in the legal reasoning of these courts appears to be the insistence that there must be specific words in the constitutional or statutory language reserving the right to make modifications and changes or no modifications can be permitted. But, the U.S. Supreme Court and virtually all state courts have recognized that the police powers of a government to impair contractual obligations for a higher public good, the health, safety and welfare of its citizens and its continued financial survival, cannot be waived, divested, surrendered, or bargained away. This is because police power is an inalienable attribute of sovereignty that is implicit in every government contractual relationship and does not have to be explicitly reserved. This article provides the legal basis for Illinois and other states to justify needed and reasonable modifications of public pension benefits that are unaffordable and insurmountable through pension reform legislation or a Constitutional Amendment. This article discusses and explains why all states can learn and should follow what the U.S. Supreme Court and virtually all state courts have vigilantly protected as the necessary and required attribute of government for the benefit of all.

One of the hallmarks of a mature and successful society is the continued capacity for growth and change. There are approximately 4,000 public sector retirement systems for state and local governments in the United State with about $3.8 trillion in assets, 14.4 million current employees, 9 million retirees and annual benefit distributions of around $228.5 billion. Unfortunately, the legacy costs have resulted in underfunded pension liabilities estimated to range between $1 to $3 trillion. This raises the pesky question of whether this underfunded liability is sustainable and affordable given total revenues for state and local governments that are only in the vicinity of $3.3 trillion annually and the costs of essential government services that are rising faster than revenues.

Some have asserted that underfunding of public pensions has been a long, chronic problem but others, like the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, have noted that things were not that threatening 18 years ago. The average funded ratio for the top third of funded pension funds in 2001 was 110% compared to 90% in 2017, a drop of 20%, the middle third of funded pension funds on average was funded 100% in 2001 and 73% in 2017, a drop of 27%, and the bottom third of funded pension funds was funded 90% on average 90% in 2001 compared to 55% in 2017, a 35% drop.

While some may place the criticism and blame on the failure of state and local governments between 2001 and 2017 to fully fund the actuarially determined contribution that would assure at least 90% funding in 30 years or less, there were other more devastating and depressing forces that fostered substantial loss, namely, two economic downturns. For example, between March 2000 to October 2002, the S&P 500 lost 49.1% in value, and between October 2007 to March 2009, the S&P 500 lost 56.4% in value. Since, in most public pension plans, the risk of investment losses is on the employer, and not shared by employer and employee, this placed additional burden on the employer to pay for losses on funds previously provided, which sounds to some like paying twice. The underfunded liabilities also increased in part due to failure to meet the return on investments sometimes pegged at 7% or 8% per annum, in these recent low-interest rate times, a bridge too far.

But not everything is dark and dismal. It appears that states like Wisconsin, Tennessee, South Dakota, Utah, Alaska, North Dakota and others, along with local governments like Washington, D.C., Denver, Scottsdale, Indianapolis, Raleigh and others have or will have successfully addressed public pension issues without extensive, prolonged disputes or litigation.

Between 2010 and 2018, over 46 states have addressed pension reform. Since 2011, there have been over 25 major state court decisions dealing with pension reforms. Over 80% (21 out of 25) of those decisions affirmed pension reform which provided reductions of benefits, including COLA (“Cost of Living Allowance”), or increases of employee contributions, as necessary, and many times citing the Higher Public Purpose of assuring funds for essential government services and necessary infrastructure improvements. Of the four states that did not permit public pension reform efforts, two states, Oregon and Montana, cited the failure of proponents of reform to prove a balancing of equities in favor of reform for a Higher Public Purpose.

In the third of the four states that did not approve pension reform, namely, Arizona, the proposal unfortunately included state court judges in the reform, which violated constitutional provisions about improper influence over judicial officers during service as well as conflicted with the constitutional provision against public pension benefits being diminished or impaired (Ariz. Const. Art. XXIX § 1(c)). However, shortly thereafter, the less than satisfying victory in the Arizona Supreme Court ruling resulted in public safety officers along with local governments and others in Arizona discovering that the Public Safety Personnel Retirement System had significantly deteriorated over the last 12 years and that failure to address reform would mean less employed public workers and financially threaten local governments. Recognizing the financial distress caused by ever increasing pension costs as well as escalating underfunded liabilities, public safety workers, state legislators and local government employers built a consensus for needed constructive reform passing legislation and a constitutional amendment to adopt the needed reforms.

Illinois was the last of the four states not permitting public pension reforms. In a series of Illinois Supreme Court decisions in 2014, 2015 and 2016, Illinois stood singularly against any modification of public pension benefits that would diminish or impair benefits of current employees and retirees.

The Illinois Supreme Court decisions pronouncing that contractual pension benefits could not be impaired or diminished as earned from the first day of employment were based in part on the questionable legal analysis that the Constitution’s Pension Protection Clause (Ill. Const. Article XIII, Section 5) does not permit reasonable modification of contractual obligations for a Higher Public Purpose. This ruling was predicated on review of the history of the 1970 Illinois Constitutional Convention and what the court purportedly perceived as unpersuasive comments and debates therein, including efforts by the chairperson of the Illinois Public Employees Laws Commission established by the General Assembly to include explicit language that the Pension Protection Clause was subject “to the authority of the General Assembly to enact reasonable modification in employee ratio of contributions, minimum services requirements and the provisions pertaining to fiscal soundness of the retirement system.” The Illinois Supreme Court interpreted the failure to incorporate the “subject to” language for reasonable modifications of pension benefits into the Pension Protection Clause and the official record to be fatal to the ability to make legislative modifications of pension benefits even for a Higher Public Purpose. According to the Illinois Supreme Court, any reservation of the police power and sovereignty of the state and its legislature must be continuously and specifically articulated as to various constitutional provisions and, if not, the reservation will not be implicitly recognized or permitted.

This reading that the “police powers” of a government to protect the health, safety and welfare of its citizens must continuously and specifically be pronounced or that right of sovereignty will be forever lost is unique and singular among analyses of “police powers” and a sovereignty’s right and duty to protect its citizens’ health, safety and welfare. Virtually every other analysis has recognized that governments, state and local, could not surrender or bargain away an essential attribute of their sovereignty, namely, the police power of a government to be able to impair contractual obligations for a Higher Public Purpose for the preservation of government and the health, safety and welfare of its citizens. The U.S. Supreme Court for over two centuries has so held that the police power to impair contracts for a Higher Public Purpose cannot be divested, surrendered or bargained away as the cases of Stone v. Mississippi, 101 U.S. 814, 817 (1880), U.S. Trust Company of N.Y. v. New Jersey, 431 U.S. 1, 23 (1977) and their progeny have so eloquently ruled. Likewise, numerous state courts consistently have so held, most recently in the State of Rhode Island’s Supreme Court decision of Cranston Police Retirees Action Committee v. The City of Cranston, et al., Rhode Island Supreme Court, 208 A.3d 557 (June 3, 2019).

The City of Cranston was in dire financial crisis in 2011. It was experiencing a high unemployment rate and over $1 billion in decreased property values, along with decreased state aid between 2007 and 2011. Then, in 2011, Rhode Island passed a law permitting modification of a pension plan that was in a “critical status” “as determined by its actuary” and the plan was less than 60% funded. The City of Cranston in 2013 passed an Ordinance for suspension of COLA for ten years for police and fire retirees. This was challenged as a violation of the United States and Rhode Island Constitutions and was settled by a consent judgment for a ten-year suspension of the 3% compounding COLA with a 1.5% COLA in years eleven and twelve with certain rights to opt out. The Cranston Police Retirees Action Committee filed suit asserting the Ordinance and settlement were in violation of the U.S. and Rhode Island Constitutions as well as a breach of contract. The Rhode Island Supreme Court affirmed the lower court decision rendered after a trial, ruling for the constitutionality of the pension reform ordinance and settlement as a legitimate exercise of police power to impair a contract for a public pension for a Higher Public Purpose. The Rhode Island courts found that there was a contractual relationship that was substantially impaired by the 2013 Ordinance, but that the impairment was permitted as reasonable and necessary to fulfill an important public purpose. The court recognized the precarious financial condition of the city compounded by a reduction in state aid rendering a budgetary shortfall that resulted in reduction in salaries, public employees and services. This government function emergency mandated the modification of pension benefits for the financial survival of the pension system and protection of the safety, welfare and benefits of citizens. The COLA suspension was the least drastic alternative and a necessary last resort.

This recent Rhode Island ruling follows a long line of U.S. Supreme Court and other state court rulings permitting reasonable modifications of contractual obligations for a Higher Public Purpose. Unaffordable public pension obligations force too many financially challenged state and local governments into raising taxes and lowering expenditures by reducing essential services or necessary public employees, thereby threatening the health, safety and welfare of citizens and the future survival of the government. Too often, this scenario of increased taxes and lowered services culminates in less actual revenues because those businesses and citizens who can leave do so, resulting in fewer taxpayers and less tax revenues. Repeated year after year, this pattern becomes a death spiral, as the financial erosion over the years of Detroit, Bridgeport, Connecticut, and others into fiscal distress so amply demonstrates.

It appears part of the Illinois Supreme Court reluctance to allow public pension benefits to be reasonably modified for a Higher Public Purpose emerged from the Supreme Court’s concern, stimulated by a veiled frustration that state income tax increases were allowed to sunset to a lower tax rate, and that, over the years, there had been an anemic attempt to raise taxes to solve the problem albeit assuming public pension benefits were affordable. No new taxes had been imposed prior to the 2015 ruling on state pension reforms. Accordingly, public pension unfunded liabilities were perceived by the Supreme Court of Illinois to be a self-inflicted crisis not borne out of the notion of poverty or inability to pay. However, since then, state income tax rates have been restored to higher levels, and the state legislature has passed legislation allowing a referendum for a graduated income tax for even higher rates on higher incomes, which should produce a projected $3 billion of additional annual income, and permitting other new taxes, such as increased gas taxes, taxes from extensive gambling expansion and marijuana sales. Any reluctance to permit reasonable and needed modifications of pension benefits due to the failure to increase taxes or the mistaken belief the unfunded liabilities are affordable should, for all practical purposes, be overcome and resolved by recent action at the state and various local levels demonstrating the limits of taxation and the unaffordable nature of certain pension benefits.

It also should be remembered that the Illinois public pension system had not been perennially at a low percentage of funding. Like many other pension systems in 2000, the Illinois public pension system’s funded ratio was 74.7%, with a $15.569 billion of unfunded liability, which was only 3.2% of the Illinois 2000 GDP. But after two economic downturns in 2001 and 2008, where the S&P 500 lost 49.1% and 56.4%, respectively, that funded ratio was only 40.1%, with the unfunded liabilities having exploded to $133.7 billion or 15.5% of the state’s GDP in 2018. While investment losses are not the sole factor for the dramatic rise in unfunded liabilities, they certainly were a contributing factor. This increase of over 862% in amount of unfunded liabilities and about a five times increase in the percentage of the state’s GDP from 2000 to 2018 changes the perception of pension affordability.

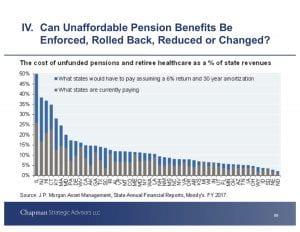

Rating agencies have expressed their concern over public pension unfunded liabilities and the adverse effect on credit ratings. Pension fund contributions by the state have risen from 8.3% of state source general funds in 2008 to about 24.5% in FY2019 with continuing increases in underfunding liabilities. Some commentators claim Illinois would have to pay level payments of about 50% of its state revenues to pay unfunded liabilities and normal costs for 30 years assuming a 6% return on investments (https://www.jpmorgan.com/jpmpdf/1320746272624.pdf). Others dispute this analysis and predication. But, Illinois’ state unfunded pension fund liability of $133.7 billion, which is 392% of the state’s general fund revenues for FY2019, raises some real concern and cries for public pension reform.

From a legal perspective, the Illinois Supreme Court appears to have rejected the application of the exercise of police powers for the reasonable modification of public pension obligations for a Higher Public Purpose because there was no explicit reservation of the police powers or the legislature’s ability to modify in the specific words of the Pension Protection Clause Article XIII, Section 5 of the Illinois Constitution.

No other state has so limited the exercise of police powers of the state by refusing to permit the impairment of contracts for a Higher Public Purpose because the constitutional provision does not have an explicit reservation of rights to exercise the police powers, a recognized essential attribute of sovereignty. In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court and virtually all state courts but Illinois have pronounced the opposite: the exercise of police powers for a Higher Public Purpose is the inalienable right of a sovereign that cannot be waived, divested or surrendered.

Indeed, as to the Illinois Constitution’s Contract Clause (Article 1 Section 16 of the Illinois Constitution), without any explicit and specific reference to being subject to impairment, the Illinois Supreme Court has permitted the exercise of police power for a Higher Public Purpose. The court found that “the Contract Clause does not immunize contractual obligations from every conceivable kind of impairment or from the effect of a reasonable exercise by the states of their police power”. George D. Hardin vs. Village of Mount Prospect, (1983) 99 Ill. 2d 96, 103. This finding by the Illinois Supreme Court was justified by citing to U.S. Supreme Court cases holding the police power impairment of contract for a higher purpose cannot be waived, divested, surrendered or bargained away and likewise is implicit in every contractual relationship a government enters into even if it is not explicitly stated or reserved.

Some have argued, as the Illinois Supreme Court has noted, that New York case law does not permit modification of public pension benefits and its constitutional pension provision is the source for Illinois’ Constitution Pension Protection Clause. However, when faced with the financial crisis of New York City in 1975 and the wage freeze under the Financial Emergency Act (“FEA”) which specifically did not include suspended contractual wage and benefit increases into the computation of earned or earnable salary for pension benefits, the New York’s highest court recognized that “Confronted with the necessity to lighten the financial burden under which the City was laboring, the Legislature’s choice of prospective impairment of executory aspects of the wage contracts was reasonable. We therefore conclude that the enactment of FEA constituted a necessary and reasonable address to a concededly important public purpose.” Subway-Surface Supervisors Association v. New York Transit Authority, 375 N.E.2d 384 (N.Y. Ct. App. 1978). Likewise, as the U.S. Supreme Court over 75 years ago recognized, purported impairment of contractual rights is not really an impairment or diminishment, but a recognition of financial reality of the inability of the government to pay and survive so that constitutional pension protections preserve practical and substantive rights, not maintain theories that are abstract paper rights and paper value not founded in the ability to pay. [See Faitoute Iron & Steel vs. Asbury Park, 316 U.S. 502, 514 (1942) (“City of Asbury Park”).] In the most practical sense, the impairment of pension contractual rights in times of dire financial distress is not a true impairment or diminishment of contractual rights under the Illinois Pension Protection Clause but a recognition of economic reality as to the limits of the ability to pay and the reality that less will be paid if the government fails.

It is now time for all states to recognize what the U.S. Supreme Court and virtually all other state courts have agreed [and even the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico in Hernandez v. Commonwealth, 188 D.P.R. 828 (2013)]: for the financial survival of public pensions and for the necessary funding of essential governmental services and needed infrastructure improvements, reasonable and necessary modification of public pension benefits in times of dire financial distress must be permitted for a Higher Public Purpose as in the recent case of the City of Cranston, Rhode Island. This is an essential attribute of government and does not need to be explicitly or specifically reserved in every clause of a constitution, since it is fundamental and implicit to the very nature of government. As the U.S. Supreme Court warned to those who claim constitutional clauses do not permit the exercise of the police powers for needed contractual modifications: “To call a law so beneficent in its consequences on behalf of the creditor who, having had so much restored to him [in a recovery plan], now insists on standing on the paper rights that were merely paper before this resuscitating scheme, an impairment of the obligation of contact is indeed to make the Constitution a code of lifeless forms, instead of an enduring framework of government for a dynamic society.” City of Asbury Park at 516.

Such use of police powers permitting impairment of contractual obligations for a Higher Public Purpose is not to be arbitrarily exercised but only utilized as a last resort, in the least drastic measure for a Higher Public Purpose after balancing the equities and alternatives for the financial survival of the public pension system and the government employer whose economic demise is fatal to public employees’ retention and retirees’ pension benefits.

The reasonableness and affordability in public pension obligations require that, in times of financial distress of governments with perceived insurmountable and unaffordable public pension obligations, there can be necessary modifications made so that citizens and businesses, who believe the situation is hopeless and desire to exit, see the hope of reasonable change so that the taxpayers necessary to find a solution stay and pay. Further, the real hope and ultimate answer of how to deal with unfunded public pension liabilities after reasonable modification are the economic growth and increased tax revenues that follow from economic development and confidence of individual taxpayers and businesses that no obligations of the government will remain unaffordable or insurmountable. The answer to unaffordable and unsustainable pension benefits, when taxes can no longer be raised without creating an exodus of taxpayers, and the reduction of services and expenses can no longer be tolerated, must be that reasonable modification of benefits is permitted for a Higher Public Purpose. The answer to such unaffordable pension obligations cannot be that the government fails because public pension benefits cannot be reasonably and necessarily modified in the least drastic manner.

The mandate of state and local governments and their reason for being is to provide essential government services at an acceptable level for the health, safety and welfare, so the government and its citizens may prosper and grow. When this essential reason for government is frustrated and prevented by unaffordable and unsustainable public pension benefits, reasonable and necessary modifications must be permitted for the Higher Public Purpose that government and its citizens continue and thrive and that, without such modifications, the continued employment life of public employees and public pension benefits are short to nonexistent. Now is the time for the capacity for growth and change where change is desperately needed.

© 2019 by James E. Spiotto. All rights reserved