By Richard A. Ciccarone, President of Merritt Research Services, an Investortools, Inc. Company

Every year since 2007, Merritt Research Services1 (Merritt Research) reports the time it takes for municipal bond borrowers to complete their annual financial audits. The results of the study consistently show slower reporting relative to industry standards of the securities markets. By now, it has been well documented that most municipal audits lag the corporate standard of 60 days by a range of three to six more months.

Slower audit turnaround times increase the likelihood that analysts will miss signals that may adversely affect municipal bond pricing and catch investors or other stakeholders off guard. In short, the useful value of the audits will become either stale or diminished, or potentially not useful at all. That concern is aggravated by the fact that the Merritt Research study evidenced that weaker borrowers generally experience longer delays than better quality credits to complete their audits.

This year’s findings are particularly disappointing. Despite a decade of placing a spotlight on the problem2, audit reporting took another step down to tie the slowest median audit time recorded over the past eleven years.

By compiling approximately 10,700 different borrowers, Merritt Research Services found that the median audit time grew to 156 days for Fiscal Year 2018, two days longer than the previous year. The last time the median audit time was this slow in the last 11 years was 2015. Over the same time period, the fastest reported time happened in 2010, when the study’s all sector median marked 147 days.

The Merritt Research Services audit timing study uses as its assessment measure the time elapsed from the end date of the fiscal year to the date in which the audit is signed. That’s different from the time period cited by other information data sources, particularly the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board’s Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA), which cited in their Fact Book more recently. EMMA measures the time elapsed from the end of the fiscal year to the time which the audit is posted on its website. As we have mentioned in previous years, borrowers may not post the audits to EMMA for days and sometimes weeks after they are finished. Common reasons may be related to official sign-off by governing officials and boards, or, in some cases, state auditors.

The Merritt Research study includes municipal bond obligors from 26 sectors, but focuses on 16 primary sectors3 which comprise the bulk of municipal bond issuance in number and asset size. Borrowers, which were less heavily represented, were largely related to non-investment grade obligors4.

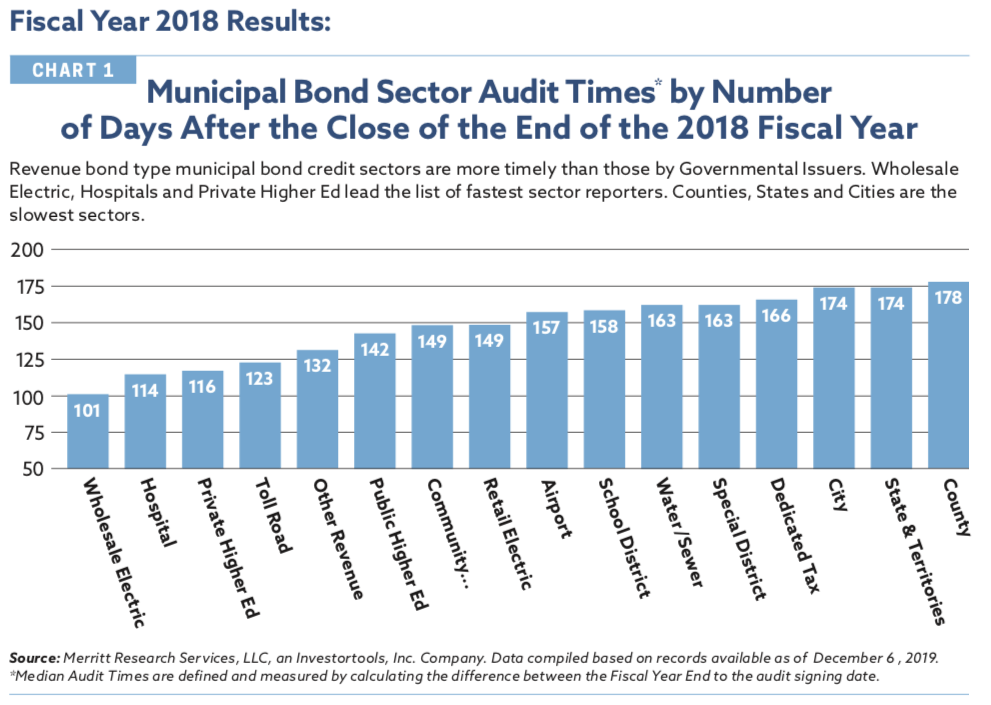

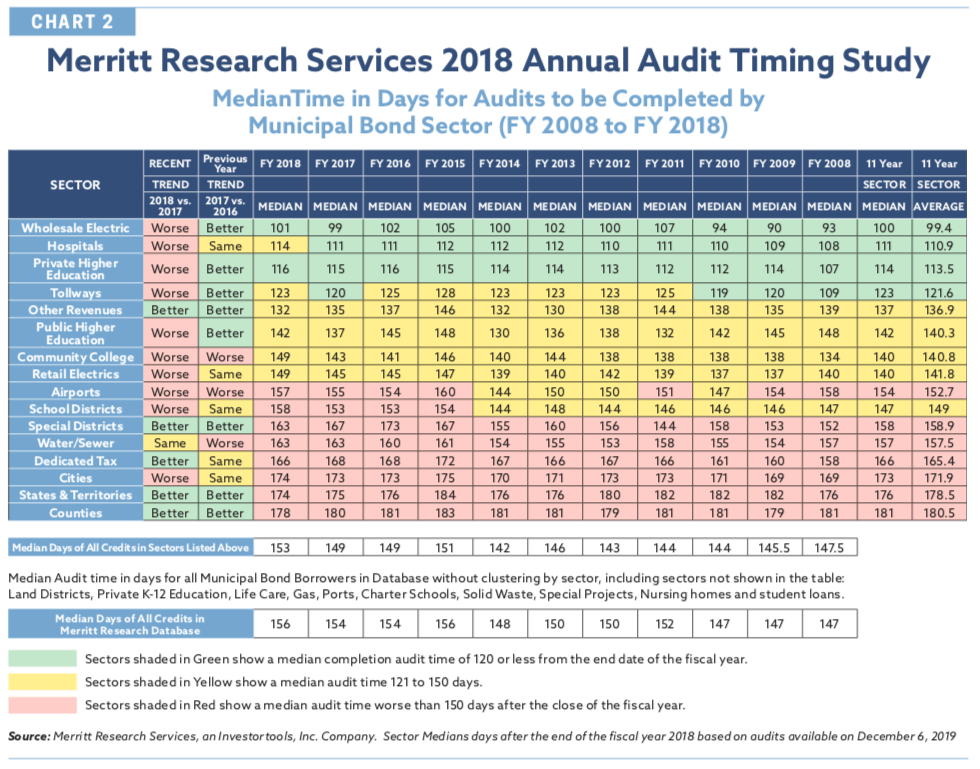

Historically the Merritt Research study has found certain municipal market credit sectors consistently do better than others. This past year, the three fastest sector median times belonged to perennial sector leaders of the pack: Wholesale Electric, Hospitals and Private Higher Education. All three have finished in that order for speediest reporting in each of the last ten years that Merritt Research has been tracking audit times. Albeit, each of these three sectors back stepped by a few days in fiscal year 2018 from the prior year.

On the other side of the coin, those municipal categories or sectors which produced the tardiest audit reporting times in the study have displayed similar sluggish finish times over the past eleven years. For the third year in a row, Counties found themselves in the worst slot with a median sector time of 178 days; though that was two days better than last year, albeit the best county sector finish in over the past eleven years. States & Territories and Cities tied for the next worst position (174 days). State & Territories finished a median day faster than in 2017, while the City sector placed a day slower. Other poky credit sectors were: Dedicated Tax, Water & Sewer, Special Districts, School Districts and Airports.

Setting a Reasonable Target for Completing a Municipal Audit

The accompanying comparison table shows median audit completion times by sector as tracked by Merritt Research since 2008 on approximately 125,000 municipal bond audits involving as many as 12,000 unique municipal bond obligors. Over the last ten years, Merritt Research categorized the sectors into three groups. The first group (shaded in green) comprises those sectors that achieved median audit times of 120 days or less from the end date of the fiscal year. The second group (shaded in yellow) includes those that finished their reports in 121 to 149 days. The third group encompasses the tardiest sectors (shaded in red) with finish times in 150 or more days after the close of the fiscal year. The color-coded pattern indicates that most sectors show consistent annual times over the past eleven years.

Although a 60-day deadline is the SEC standard for most regulated corporate bond markets, no municipal credit sector has historically come close to the 60-day mark and few reach the secondary goal (90 days) for smaller companies. The municipal bond market and the Government Finance Officers Association has held to the convention of completing audits within 120 days or less. Lending credibility to the notion that this is an achievable goal, Merritt studies showcase a significant number of accomplished borrowers who have met the 120-day standard. This timeframe for financial audits well within reach and should be set as an objective for every governmental and not-for-profit borrower.

The chart below illustrates that a little more than a quarter of 10,712 municipal bond obligors for all sectors tracked by Merritt Research completed their FY 2018 audit time in 120 days or less. By adding a month to the picture, 45% of all municipal bonds are done within 150 days.

The percent of borrowers reaching a 120-day target improves considerably when the focus is narrowed to the enterprise oriented revenue bond sectors. The sector that leads all others is the Wholesale Electric Public Power entities with nearly 80% of the audits crossing the finish line in 120 days. Sixty-eight percent of Hospitals and 60% of public higher education borrowers made the 120-day mark.

Enumerating the borrowers among municipal bonds involving governmental bodies that meet the 90-day goal, no less the 120-day goal, finds a rather sparse crowd, compared to separate agency enterprises or non-profit organizations. While no sector in the universal municipal bond market measures up to the corporate bond market, there is especially slim pickings in the governmental field.

Nevertheless, there is enough evidence that achieving the 120-day or even the 90-day rule even in the governmental area is far from impossible. Indeed, there are numerous large and small organizational standouts that regularly produce their audits in that timeframe. Look at some of the best:

Honor Roll Sample of Large Government or Not-For-Profit Orgs that finished FY 2018 audits in 90 days or less

| Municipal Bond Borrower | Sector | Days After FYE | Auditor |

| Port Authority of New York & New Jersey | Airport | 65 | KPMG, LLP |

| City of Columbus, OH | City | 87 | Plante & Moran, PLLC |

| Columbus Regional Airport, OH | County | 79 | Plante & Moran, PLLC |

| Santa Barbara County, CA | County | 59 |

Brown Armstrong Accountancy Corp

|

| Maine Municipal Bond Bank, ME | Dedicated Tax | 61 | Baker Newman & Noyes, LLC |

| Sales Tax Asset Receivable Corporation, NY | Dedicated Tax | 67 | Toski & Co, CAPs, PC |

| New York Local Government Assistance Corp, NY | Dedicated Tax | 69 | BST & Co CPAs, LLP |

| Mercy Health Corp, IL | Hospital | 45 | Wipfli, LLP |

| Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, CA | Hospital | 45 | KPMG, LLP |

| Mayo Clinic, MN | Hospital | 45 | Ernst & Young, LLP |

| Marquette University, WI | Private Higher Education | 72 | KPMG, LLP |

| Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MA | Private Higher Education | 76 | PricewaterhouseCoopers, LLP |

| Loyola University of Chicago, IL | Private Higher Education | 80 | Deloitte & Touche, LLP |

| George Washington University, DC | Private Higher Education | 80 | PricewaterhouseCoopers, LLP |

| University of South Alabama, AL | Private Higher Education | 51 | KPMG, LLP |

| University of Pittsburgh, PA | Private Higher Education | 83 | KPMG, LLP |

| Pennsylvania State System of Higher Ed, PA | Private Higher Education | 88 | CliftonLarsonAllen, LLP |

| Sacramento Municipal Utility District, CA | Retail Electric | 46 | Baker Tilly Virchow Krause, LLP |

| South Carolina Public Service Authority, SC | Retail Electric | 59 | Cherry Bekaert, LLP |

| Douglas County (Omaha) SD #1, NE | School District | 81 | Seim Johnson, LLP |

| Baltimore City Public Schools, MD | School District | 88 | CliftonLarsonAllen, LLP |

| New York State Bridge Authority, NY | Tollroad | 65 | EFPR Group, CPAs, PLLC |

| Nassau County Bridge Authority, NY | Tollroad | 74 | Morse & Company CPAs, LLP |

| Kansas Turnpike Authority, KS | Tollroad | 80 | Allen, Gibbs & Houlik, LC |

| East Bay Municipal Utility District, CA | Water & Sewer | 58 | Maze & Associates |

| Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, MA | Water & Sewer | 62 | CliftonLarsonAllen, LLP |

| JEA – Water & Sewer Fund, FL | Water & Sewer | 64 | Ernst & Young, LLP |

| Citizens Energy Group & Sub, IN | Water & Sewer | 73 | Deloitte & Touche, LLP |

| WPPI Energy, WI | Wholesale Electric | 58 | Baker Tilly Virchow Krause, LLP |

Perhaps the two best role models are cities that consistently overcome any structural governmental accounting hurdles that might stand in the way of fast turnaround times: The City of Columbus, Ohio and New York City. Columbus completed its independent audit by a private CPA firm after the end of the fiscal year in 87 days. That’s the sixth time in the last ten years in which they achieved that mark in 90 days or less. Moreover, they have been able to finish their private audits in 120 days or less for ten straight years. Columbus’ stellar record has been championed by city auditor, Hugh Dorrian, who served in that capacity for 48 years, and by his successor, Megan Kilgore. Although Ohio cities, including Columbus, are still subject to an additional statutory review, subject to an adjustment by the State of Ohio Auditor, revisions are rare if at all. In the interim, stakeholders can examine the audited books in a timely manner. New York City also deserves special mention; they finished their audit, which is extremely complex in 122 days, the 11th straight year in which they have signed their audit in 123 days or less. Although New York’s achievement is in large part due to the fact that it is motivated by a statutory requirement, it provides proof that the task can be done.

The listing above does not mean to suggest that small or medium sized governmental or not-for-profit organizations are unrepresented on the list of fast track reporters. The list of smaller borrowers that complete their books in less than 120 days is impressive and extensive (see the list of best and worst reporters by sector in the appendix to this article). The takeaway point to these examples is simply to encourage and give confidence that faster audit times for all municipal sectors are possible and not limited to one or two cases.

Significance of Governmental Accounting Rules

Some municipal revenue bond sectors such as not-for-profit hospitals and private higher education generally follow Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) accounting rules used by private sector organizations. By structure and purpose, these municipal credit sectors are more aligned to corporate-like entities and are perhaps more inclined to be run by private sector governance managers and boards.

However, many revenue bond borrowers are governmentally run departments and agencies (e.g. water & sewer, municipal electric utilities, airports and agencies with dedicated tax support) that must follow Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) rules. Frequently, these revenue bonds don’t issue independent audits. Their audits figures are incorporated into the “parent government” audit produced by a state, city or county and included in an entity-wide financial statement.

In contrast to the revenue bond sectors, which are usually single-purpose enterprises, governmental entities such as states, cities, counties often have more complex structures with sub-organizations that are probably akin to corporations with subsidiaries. Governmental organizations follow GASB accounting rules, which are thought to be more complicated because they must prepare books based on both the accrual-based approach for the entity-wide statements as well as a modified accrual basis used for separate funds, referred to as fund accounting. When GASB 34 was adopted some 20 years ago, there was also a fair share of private sector opposition to GASB 34 from rating agencies and some analysts, some of whom who sympathized with the governmental rationale and others who might have resisted change for other reasons.

The ultimate resolution of the issue resulted in a combination of the two approaches. The blend of two different approaches stems back to the time before entity-wide accounting (GASB 34) was adopted, as a compromise satisfying governments that resisted the new accrual accounting standards because most of them use cash accounting for budgeting, which was closer to the modified accrual fund accounting they had been using.

Despite the potential challenges associated with GASB 34, the entity-wide accrual based method provides a rich base of numbers that provide a truer and more holistic financial position and, to a large extent, presents longer term assets and liabilities which enables predictive analysis of the government going forward.

Governments such as cities in New Jersey that follow a statutory approach to their accounting method, which resembles the pre-GASB 34 method, not only makes it harder to get a total financial condition bottom line, but they also don’t have an argument that the audit report gets finished faster. Cities in New Jersey have a median reporting time of 218 days compared to the 174 day median for all cities in the nation.

Other Factors That Often Adversely Impact Audit Times

Some of the most frequently cited reasons for slow audit times are: (1) accounting rule changes, (2) troubled financial conditions, (3) involvement of state oversight auditors, (4) delays involving governmental component units and (5) governmental officials and governing boards that place a high priority on rapid completion of the audit document.

Accounting Rule Changes

Over the past ten years, governments frequently point to GASB rule changes, such as GASB Rule 34 on entity-wide accounting or Rules 67 and 68 involving pensions, which require substantially more data and more complex compilations, often involving input from pension plan audits. Moreover, the recent OPEB changes (Statements 74 and 75) may have contributed to longer audit times for some governments, especially school districts, in FY 2018 since the rules became effective for most local governments. In any case, the information should be welcome to not only analysts but also governance boards that now have a better grasp on this important liability issue.

Credit Ratings and Audit Timing

Audit time medians for each base rating grade5 (i.e. “AAA”, “AA”, “A” and “BBB”) generally got longer as you moved down the investment grade rating scale. The Merritt Research study showed the fastest median audit time group was most found among the best rated and highest quality borrowers. Slower completed audits were generally found among governments and organizations that were lower rated and had inferior credit metrics as measured by a number of single and aggregate credit metrics compiled by Merritt Research within its CreditScope software. That’s not always the case, but the statistical relationship is prevalent. Exemplifying the trend, the state of Illinois had the worst audit and the lowest rating of any state government. Puerto Rico still had not issued their FY 2018 audits by the time of this study.

One sector that did not show a high positive correlation to ratings was for school districts; most likely because of the so many states have state guarantee programs which often replace the underlying district credit rating with a higher rating reflecting the back up security.

Differential among Auditors

Governments or agencies audited by state auditor rather than private CPAs often have slower times in their sectors. For example, in the county sector, state audits in Alabama, Indiana, Washington, Minnesota, Oklahoma and Iowa had median audit times of over 200 days, which compares unfavorably to the national county median of 181 days. Slower state auditor reporter may have more to do with adequate audit staff available at the state level to handle so many large, medium, small and micro sized governments.

Although the Merritt Study reviewed the median audit time grouped by the independent auditor, the governmental sectors completed by larger, big name private sector auditors didn’t appear to show much of an advantage over smaller auditing firms. However, in the hospital sector, several large accounting firms, with at least 10 audit clients in the Merritt study, beat the sector medians by significant margins. PricewaterhouseCoopers, LLP had a median hospital sector time of 97 days versus the total sector median of 114 days.

Complexity of Governmental Structure

Governments with component units6, such as a convention board, a library, an enterprise etc., can complicate and extend the time to complete an audit because there are times when these audits are done by separate auditors on different auditing schedules.

Internal Complications and Culture

From time to time, major internal accounting software system changes can slow down an audit; but these situations should be one-time occurrences. Cultural and leadership influences play a significant role in accelerating the audit time or slowing it down. In some cases, governmental officials may lack the urgency to place more emphasis on the accrual accounting audit because they are more focused on cash positions aligned to their budgets. Likewise, elected officials follow the lead of their financial officials because of a lack of appreciation or understanding of the rich content afforded them by an unqualified GAAP audit. Cultural or bureaucratic resistance can be overcome by organizational or governmental leaders, which make it a high priority to complete the audit faster for the sake of good governance, transparency and accountability.

Call For Change or Face Consequences

The National Federation of Municipal Analysts has recently been calling on the SEC to act to require municipal bond borrowers to hasten the public release of financial reporting. Senator Kennedy of Louisiana has been an outspoken critic of the late audits as well. The SEC is examining the issue and its alternatives.

Municipal pricing differentiation is almost always inconspicuous relative to audit times in large part due to market conditions caused by insufficient supply relative to the demand for municipal bonds, infrequent default history, low interest rates in general and relatively modest interest rate variances tied to credit quality. That could all change if one or a combination of these factors reverse.

For now, late audits should and may already factored into borrowing or trading yield levels on low quality municipal bonds. The problem in proving that point is that breaking out how much the proportional difference is due to quality weaknesses vs. late audit availability is blurred by the more dominant quality factor. Certainly, two year old audits in Puerto Rico exacerbate investor confidence and demand. Late auditing appears to be a frequent symptom of weaker quality as well as a notable flaw in good governance.

The Merritt Research study provides ample of evidence that a 120-day standard is a reasonable target that can be achieved by all borrowers in the near term if issuers put forth the effort. If municipal bond issuers procrastinate to meet that target, it is more likely that the government will mandate it. In order to avoid regulation of audit times, bond issuers should act now to make it a higher priority to accelerate the completion of audits and release them to the market promptly. Rating agencies and investors have the tools to penalize non-compliance, but they must choose to use them. Chronically late audit times should be reflected in lower bond ratings and higher issuer borrowing rates.

Read the full Merritt Research Report on 2018 Audit Timing — includes statistical appendix. Click Here.

Related Articles in MuniNet Guide:

- Fiscal Year 2017 Municipal Bond Audit Times Are Still Too Slow (Dec 05, 2018)

- State and Local Government 2015 Audit Times Take a Step Backward (Nov 21, 2016)

- Change Doesn’t Come Easy for Municipal Bond Audit Timing (Oct 27, 2015)

- Who Files Annual Financial Audits Faster: Large or Small Municipal Bond Issuers? (Oct 18, 2013)

- Does Municipal Bond Credit Quality Impact Annual Audit Times? Oct 2, 2013

- Leading by Example: Syracuse University Is Fastest Municipal Borrower to Complete Financial Audits Sep 27, 2012

- Most Municipal Audits Still Slow, Despite Push for Timely Transparency Sept 19, 2012

- Which Municipal Bond Sectors are Fastest, Slowest to Complete Financial Audits? Oct 5, 2011

- Study Examines Municipal Audit Turnaround Time Nov 1, 2010

1 Merritt Research Services became a wholly-owned Investortools, Inc. company on October 31, 2019.

2 Merritt Research Services’ first annual study was published in November, 2010 in a report entitled: “Just How Slowly Do Municipal Bond Annual Audit Reports Waddle in after the Close of the Fiscal Year?”

3 Municipal bond credit sectors that received primary focus by Merritt Research included Airport, City, Community College, County, Dedicated Tax, Hospital, Other Revenue, Private Higher Ed, Public Higher Ed, Retail Electric, School District, Special District, State & Territories, Tollroad, Water & Sewer and Wholesale Electric. Sectors in bold are considered standard primary coverage Merritt Research sectors. Non-bold sectors are tracked by Merritt Research only on a custom request basis; sample sizes are smaller relative to the entire sector subset.

4 Other sectors not separately tracked for median times were Land Districts, Private K-12 Education, Life Care, Gas, Ports, Charter Schools, Solid Waste, Special Projects, Nursing Homes and Student Loans.

5 Rating grade medians were based on the lowest of either Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s municipal bond ratings by obligors (creditors). For Moody’s and S&P ratings, Merritt Research used the highest or senior debt rating for individual ratings (rating groupings did not distinguish fine tuning segmentation to include, “+” or “–“ or “1”,”2” or “3” rating variations).

6 GASB defines Component units as legally separate organizations, often governmental, for which the elected officials of a primary government are financially responsible.

© Merritt Research Services, LLC is an Investortools, Inc Company. Merritt Research is an independent municipal bond data and research provider, distributed by Investortools Inc.’s CreditScope software package. Established in 1986, Merritt Research is the first and the oldest subscription based municipal bond credit database and software package available in the municipal market.