By James E. Spiotto

This is Part 4 in a 4-part article series on the Post-Fiscal Crisis State and the next fiscal crisis considerations. The information and charts come from a presentation given at the Government Finance Research Center’s conference entitled “Ready or Not? Post-Fiscal Crisis/Next Fiscal Crisis” held on May 2-3, 2019 at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

To read part 1 click here. To read part 2 click here. To read part 3 click here.

Slower population, job, personal income and GDP growth can be reversed by focused economic development the accentuates the strengthens of the State and Local Governments. Delayed infrastructure improvements and failure to reinvestments in desired and needed governmental services have led to the slower growth in all areas. There are Trillions of dollars of needed infrastructure investments by State and Local governments in the next 5 to 10 years that can make all the difference in growing and expanding the economy and increasing population, jobs, personal income, tax revenues and GDP. Studies have shown every good hard dollar investment in infrastructure will yield over $3.00 in economic benefit over 20 year most front end loaded. Every new infrastructure improvement employee creates one or more indirect jobs to supply goods and services for that infrastructure job and induces the new employed worker to spend new found funds that creates new jobs for the newly purchased goods and services. This job multiplier and the resulting increase in jobs, income, tax revenues and GDP is the high tide that raises all boats. The use of Foreign Trade Zones in States and Local Governments create zones where foreign manufactured parts can be imported into the zone without the 20% tariff for remanufacturing, assembly to further processing by United States workers and companies. If we turn on these Lights the future will be bright.

The new reality of tariff wars and 20% surcharges on foreign manufactured parts and goods:

The tax reform of 2018 created a 20% surcharge on foreign manufactured goods or parts coming into the United States. Recent U.S. tariffs on imported steel and aluminum has triggered reciprocal tariffs on U.S. exports to foreign countries. The ability to attract new business and help current businesses in the Midwest to expand will depend on the states’ ability to deal with this new reality. One such method is the use of foreign trade zones.

What is a Foreign Trade Zone?

Around the world there are specially designated areas within countries’ borders that are established and controlled by national legislation and through which the receiving, handling, manufacturing, repurposing, and exporting of goods can occur free from import duties and taxes. These areas are usually known as free trade zones.

The Foreign-Trade Zone Act of 1934 as amended (“Act”) created the possibility for this type of area within the United States of America. They would be known here as foreign trade zones (“FTZ”). According to the Regulations of the U.S. Foreign-Trade Zone Board (19 CFR Part 400):

“[A] Foreign Trade Zone (FTZ or zone) includes one or more restricted-access sites, including subzones, in or adjacent to a [Customs and Border Protection or CBP] port of entry, operated as a public utility under the sponsorship of a Zone Grantee authorized by the Board, with Zone operations under the supervision of CBP.”

According to the U.S. Foreign-Trade Zone Board Annual Report to Congress:

“[A] Foreign Trade Zone is created when a local organization, such as a city, county or port authority, applies to the FTZ Board for a grant to establish and operate a zone to serve a specifically defined geographic area. Upon approval of the zone by the FTZ Board, the organization becomes known as the FTZ ‘grantee’. Grantees are then able to submit applications to the FTZ Board to establish FTZ sites or subzones for use by companies in that area.”

Use of foreign trade zone status (with industrial parks and alternation site framework):

A city or public corporation can apply for Foreign Trade Zone (“FTZ”) status which must be approved by the Department of Treasury and Commerce: Foreign Trade Zone Act 19 U.S.C.§81(u), Foreign Trade Zone Board Regulation 15 C.F.R.§400, and Custom Regulation 19 C.F.R.§146. Alternation Site Framework (“ASF”) gives participating zones greater flexibility to a much simpler, faster minor boundary modification procedure to designate locations where companies are ready to use FTZ. FTZ maintain and create jobs and involvements in the U.S. as opposed to in a foreign country by customs/tax financial savings. FTZ stimulate American economic growth and development because FTZs encourage companies to continue to expand their operations in the United States.

What are the benefits of a FTZ?

Both manufacturers and distributors can benefit from operating in a FTZ. Because FTZs are considered outside of customs territory, businesses may import product into a zone without paying customs duties. Duties on products destined for domestic destinations are deferred until products leave the zone, and products that are re-exported, either in original form or as part of a product made in a zone, are generally exempt from customs duties. With approval from the Foreign Trade Zones Board, a manufacturer may elect to pay duty on an imported component either at the duty rate applicable to the component or at the duty rate applicable to the finished product. In either case, U.S. value added in the zone is not subject to duty. In an inverted tariff situation, one in which the duty rate on the finished product is lower than that on the imported component, manufacturing in a FTZ results in a lower overall duty to the manufacturer.

A FTZ helps attract foreign manufactures looking to reduce the retail sale price of the product by assembly or manufacturing in a FTZ in the United States thereby avoiding the 20% surcharge or other tariff and taxes in whole or in part. This benefit of a reduced cost of manufacturing can help create new, good jobs in a FTZ created by foreign manufacturers or domestic distributors to assemble the parts or manufacture the product in the FTZ in the United States. The parts and machines to manufacture come into the FTZ duty free and there is a negotiation of a duty on the finished product that is generally far more favorable than the duty on the foreign assembled or manufactured products. The new jobs created generally promote related manufacturers of parts or components as suppliers to participate in the FTZ, thereby increasing even more jobs in the FTZ. This process produces the job multiplier of direct, indirect and induced jobs of two to five or more jobs. There is the job created to produce or assemble the product (direct) and the job created for supplies, goods and services provided to the FTZ manufacturer for manufacturing or assembling (indirect job) and jobs created by the new worker spending their salaries for goods and services (induced jobs).

Companies that operate in FTZs import parts, material, components or equipment for manufacturing, and they finish the goods or parts for distribution in the U.S. or to be exported. The benefit of FTZ status is that the custom duties on foreign parts, materials, components or equipment imported by the company operating in the FTZ either are eliminated or substantially reduced or deferred so that generally the only duty is on the finished product which is a significant reduction in duty expenses. This applies to foreign products admitted into the FTZ for storage, exhibition, assembly, manufacture and processing.

The Midwest already has FTZs in most states:

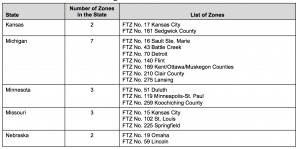

There are over 230 FTZs in the United States with nearly 40 sub zones. There are 50 FTZs in the 12 Midwest states with the highest number (30) in four states, namely: Ohio (9), Illinois (8), Michigan (7) and Indiana (6). Use of the FTZ combined with industrial parks could help local tax issues by creating not only increased economic activity but also creating additional employment opportunities, business and infrastructure expansion. All of this creates additional tax revenues that should ease tax and leverage problems. Note: tax incentives to relocate to the FTZ can be costly. See Foxconn negotiations with Wisconsin.

Examples of an approach to FTZs and economic development that may work for distressed municipalities:

Upside Chicago – Creation of 10-18 industrial parks in the Chicago area creating 20,000 new good jobs for about 100-140 new or relocated companies and the City of Pittsburg’s recovery plan.

The use of natural attributes of Chicago for business development:

Chicago is the center of commerce especially as far as Transportation (major rail, land and air as well as water). Chicago USA is the second largest manufacturing metropolitan area in the U.S.A. and has a long history in manufacturing given its central location and ease of transportation. Educated workforce. Chicago has an educated workforce and the ability to educate and train new workers for the new manufacturing models of the future.

Development of Upside Chicago:

The Concept was created by local business professionals on a pro bono basis who had experience with operations, manufacturing, finance, insurance and Special Economic Zones, both domestically and internationally. The factors that produced lower cost for production and distribution of goods that led to the development of the Maquiladora in Mexico and Special Economic Zones in China and elsewhere are now present in Chicago. For Labor and Freight Intensive Manufacturing the cost of shipping can be 8-16% or more of Sales Price while labor can be 15-22% of Sales Price. A savings of 3-6% or more of sale costs is the equivalent of reducing employment cost by about 25% or more.

Chicago’s unique transportation facilities could reduce shipping and handling costs by 4-6% or more of Sale Price depending on the comparative shipping locations. Establishing a non for profit special purpose entity that would be the Industrial Parks Coordinating and Supervising Managing Agent (“Park Agent”) that would offer manufacturing site with cost efficiencies for smaller manufacturing companies, 100-250 employees by shared services (similar to condominiums for manufacturing) where building outside maintenance, public safety, freight services, public safety inspection, insurance (worker compensation and other general liability) etc. are shared costs with the leverage in negotiation of the mega manufacturer with 20,000 workers. In additional all available financing assistance through local government economic development incentives, site improvement assistance and financing structures would be pursued to the extent appropriate.

The main focus would be the lower skilled jobs with the higher shipping and handling costs such as auto reclamation, parts remanufacturing (roughly 2,100 companies in U.S.A.), recyclers (about 3,000 companies in USA, 103,000 employees), return processing (or online sales return processing), data storage and processing center etc. Given the projected savings (from reduced shipping costs and shared services savings as well as possible governmental incentives), it would be very attractive to these companies to move to Upside Chicago. More than sufficient supply of high-quantity, low-skilled and semi-skilled workers in Chicago area — the commutable area has at least 1.4 million workers.

Companies can envision themselves in a clean, modern, safe, digitally wired, next generation industrial park opposed to being attracted to disparate (perhaps) degraded individual site. Park companies will bond with each other for the benefit of all. They will learn from each other with regard to workers, safety, security, environmental compliance, security, etc. The bundled economics benefits of Upside Chicago gives small companies the benefit of a larger enterprise and increased free time by reducing or eliminating time which would have been spent negotiating individually on shared services provided by the Park Manager.

Projected economic benefits of Upside Chicago concept:

Upside Chicago and the goal of creating 20,000 new manufacturing jobs (with additional indirect and induced jobs) should over the long run create 44,000 jobs more or less (direct, indirect and induced job multiplier), increase state and local taxes by $426 million or more, help improve infrastructure and government services with increase tax revenues in addition to the Industrial Park site improvements and infrastructures, and produce an estimated economic benefit of the Industrial Park Program of over $8 billion.

The Pittsburgh story and recovery efforts:

Between 1950 and 2000, Pittsburgh lost the same percentage of population as Detroit with similar adverse affects to its economy and financial condition. In the early 2000s, the City began a program of economic development and in December of 2003 initiated the use of Act 47 Pennsylvania’s municipal recovery plan process for financially distressed municipalities. Pittsburgh in 2003 was downgraded by Standard & Poor’s (“S&P”) five levels from A- to BB and other rating agencies took similar action. (Pittsburgh was AA in the 1960s and 1970s and dropped to A in 1981 and the A- in 1994.) This was the lowest rating of any major city at that time. In the 2000’s Pittsburgh began a campaign to increase job creation and employment in Pittsburgh. As a result, between 2004 to September 2013, Pittsburgh increased employment by 56,220 in such areas as technology, high tech, med tech and energy.

In October 2013, S&P, after analysis of the City of Pittsburgh and efforts of stimulating its economy and creating new jobs, raised its rating on Pittsburgh debt from BBB to A, an increase three levels from the 2006 rating upgrade from BBB- to BBB.

Fiscal distress of or perception of risk of nonpayment by government begets higher cost of borrowing and even loss of access to the market:

On March 2, 2012, Greece had a ten-year bond annual yield of 37.1% and in July, 2015, after the third attempted bailout and austerity package being implemented, Greece’s annual yield is still over 10.5% with a 52 week range of 5.5% and 19.5%. Since 1826, Greece has defaulted on its sovereign debt since 1826 at least five times prior to its recent financial crisis (1826, 1843, 1860, 1894 and 1932). Brazil, a large developing economy which defaulted or restructured its sovereign debt eleven times since 1826, the last time in 1990, had an average ten-year bond annual yield between 2006 and 2015 of approximately 12.3% with all time high of 17.91% in October, 2008.

Puerto Rico, given its recent financial distress experience, had yields on its ten-year G.O. bonds exceeding 10% in February, 2014. At the same time, other sovereigns experienced unusually low bond annual yields of 2.27% for U.S.A., 1.52% for Canada and 1.03% for France. A review of the adverse effect of state and local governments trying to balance the budget by defaulting or devaluing the currency has been met with harsh consequences, and the inability to pay due to financial distress, which is understood by the market, raises borrowing costs and could even deny market access.

Traditionally, the spread in the municipal market between strong credits (top investment grade) and significantly weak credits (lower non-investment grade) was 200-300 basis points. (See e.g., approximate 200 basis point trading spread between Detroit sewer and water with and without Chapter 9 threat and Chicago sale tax securitization approximate 275 basis point lower than similar Chicago maturities.)

Being classified as a weaker credit increases the cost of the borrowing by 25% or more of the face amount of debt and should be avoided if possible. To a state or local government, a 200 point per year or 2% more interest cost a year on a 20-year bond with a bullet maturity would be 40% more of the principal amount paid as interest over 20 years. Put another way, on a billion dollar debt issue with a 20-year maturity and a bullet payment of principal at maturity, a 2% additional interest cost per annum would be a present value at a 5% discount of about $250 million or 25% of the face amount. That is $250 million not available to state or local government to pay needed infrastructure improvements, public services, worker salaries, retiree benefits or tax relief to its citizens.

This perception of risk can stress taxes and leverage issues. The perception of risk can cause the inefficient use of the revenues to unnecessarily pay large interest cost equal to 60% or more of the original principal amount.

This increased cost of borrowing can exacerbate already existing leverage problems. The solution is to use market-accepted assured payment structures that reduce risk of nonpayment and lower cost of borrowing such as statutory liens, special revenues, securitization of tax receivables, irrevocable statutory or constitutional mandates, set asides and priority of payments.

What is a statutory lien or a special revenue pledge?

Generally, the statute from which the statutory lien arises contains language such that the force and effect of the statute creates the interest in the dedicated revenues or proceeds to pay the debt without need of further action by the issuing governmental entity. It may also provide for the priority of payment, a first lien or provision that the dedicated pledged revenues can only be used to pay the debt or in the order specified in the statute or authorizing documents. It may also provide an intercept or segregation of the revenues or require a governmental entity or officer to collect and pay over to a special account or to the bond trustee.

Additionally, some states provide by statute that the state or local government, upon issuing debt pursuant to a specific state statute, automatically grants a lien (dedicated revenues or proceeds only to be used to pay the debt prior to any other use) on specified property, proceeds or tax revenue for the payment of the debt so incurred. The granting by a local government pursuant to a local ordinance, without more, is unlikely to give rise to a statutory lien.

Section 902(2) of the Bankruptcy Code defines Special Revenues as:

- (A) receipts derived from the ownership, operation, or disposition of projects or systems of the debtor that are primarily used or intended to be used primarily to provide transportation, utility, or other services, including the proceeds of borrowings to finance the projects or systems;

- (B) special excise taxes imposed on particular activities or transactions;

- (C) incremental tax receipts from the benefited area in the case of tax-increment financing;

- (D) other revenues or receipts derived from particular functions of the debtor, whether or not the debtor has other functions; or

- (E) taxes specifically levied to finance one or more projects or systems, excluding receipts from general property, sales, or income taxes (other than tax-increment financing) levied to finance the general purposes of the debtor.

What are the benefits of statutory liens and special revenues?

These types of financings are intended to create predictable priorities in Chapter 9 so municipal bond market participants can be protected by a predictable result. Outside of a Chapter 9 proceeding, participants would be protected through enforcing payment by writ of mandamus or other remedies and the fact that a governmental officer must comply with the mandate of state law or suffer the penalties. In Chapter 9, there is intended to be established priority and assurance of payment so that governmental bodies suffering from temporary illiquidity would have access to the municipal bond market with a dedicated source of payment that would survive Chapter 9. (See legislative history of 1988 Amendments to the Bankruptcy Code regarding solving the dilemma of the City of Cleveland in 1978.)

How are special revenues to be treated in Chapter 9?

A special revenue pledge is to be unaltered in a Chapter 9 proceeding, and the timely payment of the pledged revenues by the municipality is required by the Bankruptcy Code. Special revenues were intended by the 1988 Amendments to the Bankruptcy Code to be unimpaired in Chapter 9 and the debt holders to receive the benefit of the bargain. This unimpairment was respected in the Chapter 9 proceedings of the Sierra Kings Health Care District Chapter 9 (Eastern District of California), Jefferson County, Alabama (Northern District of Alabama) Stockton, California, and Detroit, Michigan (for those who continued to hold Water and Sewer Revenue Bonds, the case reaffirmed the unaltered status and timely payment of special revenue pledges in a Chapter 9 proceeding).

How are statutory liens treated in Chapter 9?

Statutory lien is to be unaltered and timely paid. A statutory lien should remain unaltered in a Chapter 9 proceeding, and there is a continuing right to be timely paid after the filing of a Chapter 9. Chapter 9 cases recognize the unaltered treatment. Such unimpairment was recognized in the Chapter 9 proceedings of Orange County, California in 1994 (delay in payment due to appeal and reversal of Bankruptcy Court as to effect of a statutory lien) and the Sierra Kings Health Care District Chapter 9 in 2009 (relating to General Obligation Bonds). A number of states have statutes containing statutory lien provisions. See e.g., Rhode Island, California, Colorado, Idaho, Louisiana and New Jersey (Municipal Qualified Bond Act). Statutory lien legislation is pending in Michigan (HB 4495), Nebraska (LB 67) and Illinois. See Appendix which is taken from the 50 State Survey in the recently released Second Edition of “Municipalities in Distress?” for breakdown of statutory lien categories for further analysis).

Legislative history of the 1988 Amendments to Chapter 9 support the unaltered status of statutory liens and special revenues:

The Senate Report for the 1988 Amendments notes:

“In the municipal context, therefore, the simple answer to the Section 552 problem [lien or pledged termination on filing] is that Section 904 [limitation on jurisdiction and power of court] and the tenth amendment should prohibit the interpretation that pledges of revenues granted pursuant to state statutory or constitutional provisions to bondholders can be terminated by the filing of a chapter 9 case. Likewise, under the Contract Clause of the Constitution (article I, section 10), a municipality cannot claim that a contractual pledge of revenue can be terminated by the filing of a chapter 9 proceeding.” S. Rep. No. 100-506 at 6 (1988).

The Senate Report accompanying the special revenue provisions provides:

“Finally, the amendment insures that revenue bondholders receive the benefit of the bargain with the municipal issuer, namely they have the unimpaired right to the project revenue pledged to them.” Senate Report 100-506 at 12.

The San Jose School District case. Accordingly, the statutory lien pledge of ad valorem tax revenues for the timely payment of the Unlimited Tax General Obligations (“ULTGOs”) debt service was not interfered with in the San Jose School District case and is not to be interfered with under Chapter 9 as the legislative history for special revenue treatment so provides. Past Supreme Court rulings and provisions of Chapter 9 support this. This legislative history noted the principles that are embodied in Sections 903 and 904 of the Bankruptcy Code and the Tenth Amendment as recognized in the Supreme Court of the Ashton and Bekins:

That the statutory lien cannot be terminated nor the mandated payment impaired so that revenue subject to the statutory lien or special revenues must be paid timely as intended to the debt holders.

The cloud raised by the recent Puerto Rico decision:

On January 30, 2018, the Federal District Court hearing the Puerto Rico Debt Adjustment proceeding under PROMESA entered a ruling that startled the municipal market by pronouncing that, unless the municipality voluntarily decided to make the timely payment of special revenues pledged to the bondholders, the payment was stayed during the bankruptcy proceeding. On March 26, 2019, the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit affirmed the lower court ruling. There is now pending a petition for rehearing en banc.

This decision of the lower and appellate courts in the Puerto Rico PROMESA case that pledged special revenues would not be paid during the Chapter 9 proceeding unless the municipality as debtor chooses to do so is contrary to the decisions or practices of the numerous Chapter 9 courts (including in Jefferson County, City of Stockton, Detroit, Sierra King Health Care District, San Jose School District and other Chapter 9 cases). No Chapter 9 bankruptcy court has interpreted Section 922(d) to prohibit the payment of pledged special revenues as collected to revenue bondholders during the pendency of a Chapter 9.

The Puerto Rico courts’ ruling was such a shock some contended it should only apply to PROMESA and U.S. territories and not to municipalities of states. But the Federal District Court did not appear to limit its ruling or interpretation of sections of Chapter 9 of the Federal Bankruptcy Code to just PROMESA ,and its analysis of the language specifically discussed sections of Chapter 9 that had applicability to PROMESA. There appears to be no quick fix to the conflicting positions of all Chapter 9 courts supporting the timely payment of pledged special revenues to bondholders in a Chapter 9, and the PROMESA court ruling that special revenues will be paid to bondholders on a timely basis during a Chapter 9 only if the municipality so chooses.

Could the municipal markets understanding of special revenues and the prior Chapter 9 court rulings on special revenues and the 1988 Amendments including Section 922(d) be so wrong? The answer is NO! A motion for rehearing en banc is pending before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. Since all prior Chapter 9 court rulings were contrary to the Puerto Rico decision and the 1988 Legislative History clearly supports the reversal of the Puerto Rico decision, the First Circuit ruling should not stand.

That concludes this article series. Thanks for reading!