Legacy costs, especially for mature cities, can carry a long lasting burden on the finances of municipalities challenged by massive unfunded pension liabilities and retiree health care costs. Those cities most affected by these burdens also typically experience high levels of fixed costs required for debt service and OPEB payments in addition to their pension contribution requirements. Measured against their total spending (i.e. governmental activities expenditures), high fixed costs place a squeeze on current tax dollars to cover operations, provide for public safety and the costs to repair and replace infrastructure.

Legacy costs, especially for mature cities, can carry a long lasting burden on the finances of municipalities challenged by massive unfunded pension liabilities and retiree health care costs. Those cities most affected by these burdens also typically experience high levels of fixed costs required for debt service and OPEB payments in addition to their pension contribution requirements. Measured against their total spending (i.e. governmental activities expenditures), high fixed costs place a squeeze on current tax dollars to cover operations, provide for public safety and the costs to repair and replace infrastructure.

Once they are in place, trying to lower legacy costs by restructuring public pensions can be like moving a mountain whenever benefits and expectations are already locked into the mindset of active and retired employees. The city of Cincinnati serves as a good example of a city that in recent years has tried to tackle the problem. In its case, it took nearly seven years of confrontation and negotiation to make the effort happen.

Cincinnati’s Collaborative Agreement

Out of the city’s four pension plans, the City of Cincinnati maintains one single employer plan, the Cincinnati Retirement System (CRS), which has been in place for the benefit of its employees since 1931. The CRS is the largest of all its plans and the source of the city’s highest unfunded pension liability. The city’s other three plans are smaller liability cost sharing multi-employer plans.

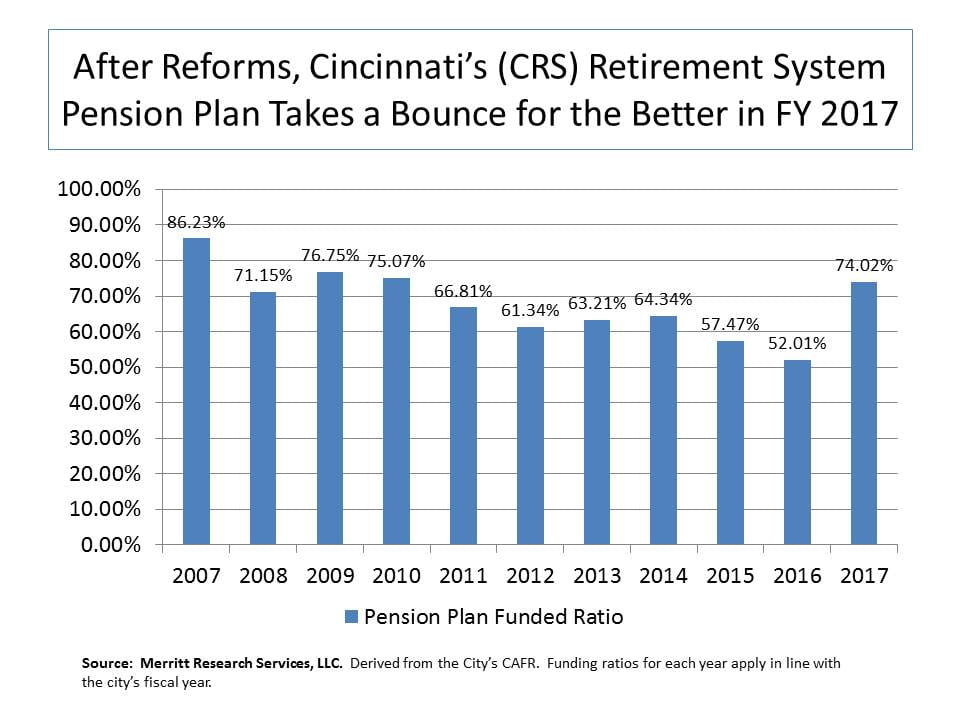

In the aftermath of the credit crisis, subsequent to 2007, it became evident that the CRS pension plan was headed on a serious negative path that threatened to spiral downward. Taking the initiative to stem a potential fiscal crisis, the city initiated negotiations with its unions, which led to a contentious standoff. After nearly five years of litigation to reach a Collaborative Agreement, it took another 15 Months of negotiations to reach a final deal. On October 5, 2015, U.S. District Court Judge Michael R. Barrett granted final approval. Coming to terms was no easy task but the issue gained traction as a recognized crisis when the Governmental Accounting Standards Board’s new accounting rules went into effect in 2015, which required the plan to automatically reduce its discount rate from 7.5% to a blended discount rate of 5.59%. Under GASB’s new pension rules, a reduction in the discount rate is required and triggered whenever the plan’s assets were deemed insufficient to cover all of the plan’s retirement benefits. The net impact of the discount rate change on Cincinnati’s Retirement System plan reduced the overall funding rate to only 57.5% as reported in the 2015 CAFR from 64% in the previous year, a trend that threatened to go even lower in future years.

The agreement that went effective immediately was designed to “share the pain” across all parities with the city making major new contributions and the retirees receiving reduced benefits.

Key actions taken as a result of the negotiation to resolve the $862 million unfunded pension liability were:

- Transferring $200 million from the healthcare trust into the pension system by reducing health care benefits to employees;

- Make a $39.1 million city cash infusion into the pension system;

- Guarantee an employer contribution for 30 years (The City is to contribute 16.25% of payroll into the pension system annually. Historically the contribution rate had been under ten percent within the last 20 years);

- Reduce COLA spending from 3% compound to 3% simple;

- Suspend COLAs for all employees for three years: three years and current retirees did not receive a COLA in fiscal years 2016, 2017, and 2018. All future retirees will not receive a COLA during their first three years of retirement;

- Extend the retirement age and years of service requirement for some current employees

The primary goals of these actions were to: Stabilize the overall financial position of the CRS so that both current and future retirees can expect to receive meaningful and competitive benefits in the future, specifically pension and healthcare benefits. The pension trust fund will be funded at actuarially appropriate levels, with the goal of establishing a projected 100 percent funding ratio in 30 years and remain funded for the balance of the Collaborative Service Agreement (CSA).

The impact of the changes enacted in 2015 were spread out over time and not visibly reflected in the short term. In the city’s most recent FY 2017 audit, the fixed cost percentage share of the city’s ratio of current debt service, contributions to pensions & OPEB to governmental activities expenses, increased from 17.1 % in FY2016 to 36.6% in FY2017. However, the relatively big jump in the fixed cost ratio was distorted by the downward impact on total expenses associated with the Collaborative Settlement Agreement, which effectively cut total expenses by reducing annual contribution requirements related to lower pension and healthcare expenses. The city’s business enterprises also saw their total expenses adjusted to reflect the reduced pension costs as a result of the CSA pension reduction requirements. The net impact of these 2015 changes produced substantial improvement in the plan’s total pension liability as evident in the most recent city audit in which the problematic Cincinnati Retirement System Plan funding ratio took a significant upturn to 74% in FY 2017 from 52% in 2016.

It remains premature to say that Cincinnati has cured its problem with legacy liabilities. What can be said is that it has made major headway to secure a more manageable outlook and a dose of optimism for both its pensioners and its taxpayers.

Michael J. Ross