Are Fixed Costs Squeezing Out State and Local Governments’ Ability to Deliver Public Services?

In the back of every analyst’s mind, whenever they assess public pension risk and the potential for fiscal stress, is the question of whether or not the annual cost to pay for retirement expenses will squeeze out a government’s ability to cover essential public services and infrastructure needs. In reality, pension liabilities must be considered jointly with both outstanding obligations to cover retiree health care promises (other post-employment benefits, or OPEB) and bonded indebtedness. Combined, these constitute the basic fixed costs of government.

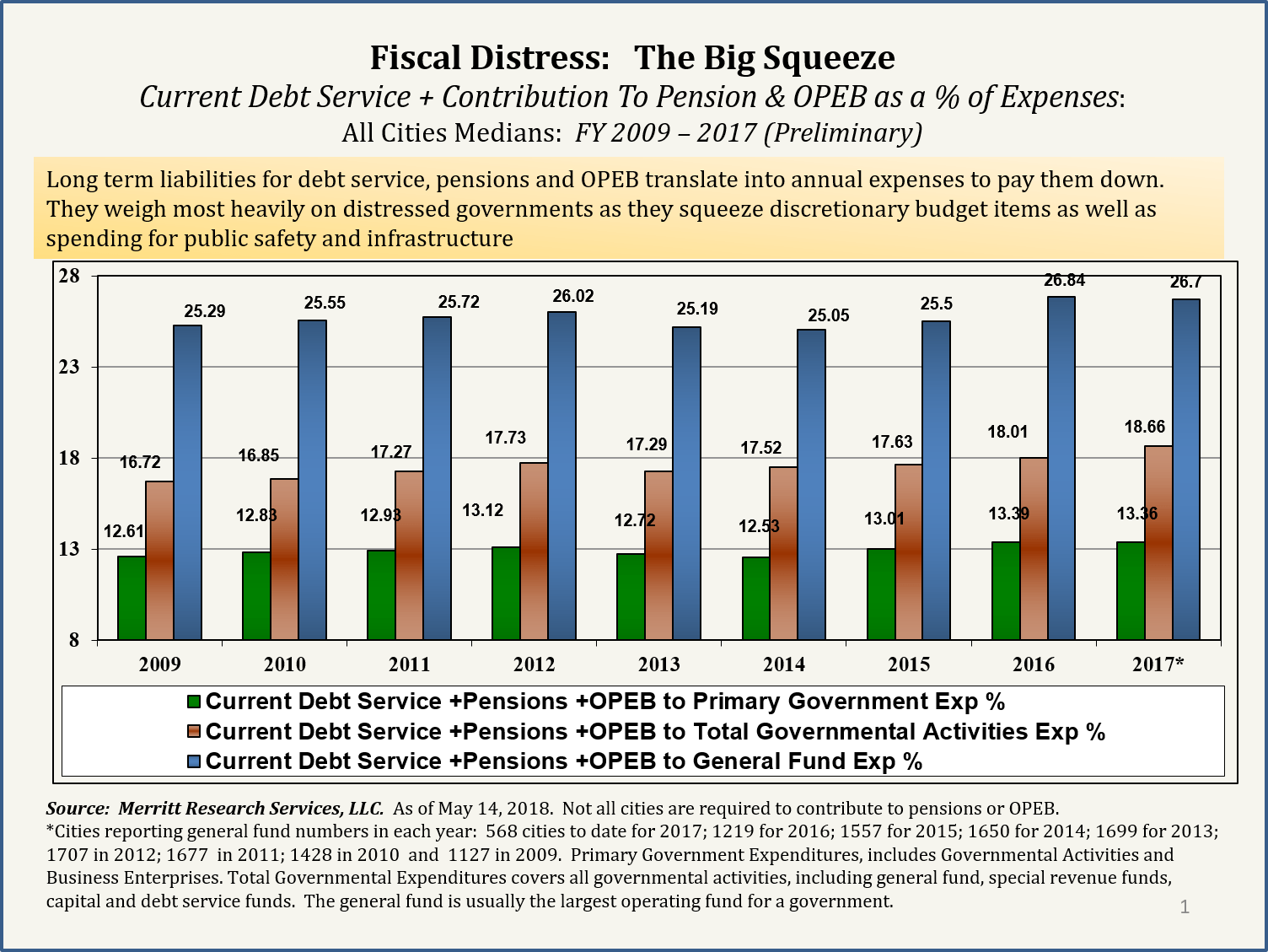

In the accompanying chart, the combination of long term liabilities for pensions, OPEB and debt service are compared to three different spending measures: (1) general fund expenditures (normally the largest operating fund of a government), (2) total governmental activities expenses (combining all government expenses, including general, special revenue, debt service and capital improvements funds), and (3) all primary governmental expenses (includes governmental activities expenses and enterprises, such as water and sewer activities). A fourth approach could involve the consolidation of all governmental funds, which is similar to the governmental activities expenses except that it does not include some non-cash items such as depreciation and pension expense.

In recent years, cities have seen a gradually larger portion of all expenses tied up to pay fixed costs. Depending on which approach to governmental accounting is used, the city median fixed share of costs generally ranges from 13% to 27% for the most recent fiscal year.

The most commonly referenced comparison applies to just the general fund, the largest discretionary fund for nearly all governments. Here, fixed costs to pay outstanding long-term liabilities has grown to a substantial 27% share of general fund expenses in FY2016 and FY 2017, up from 25% in 2009. This ratio needs to be in put into perspective; the burden relative to the general fund may be statistically exaggerated, as many cities pay their debt service (one of the basic fixed cost elements) out of the debt service fund rather than the general fund.

The ratio relating to all governmental activities expenses probably reflects a more accurate comparison to overall spending and true economic cost. In this case, the ratio has risen from 16.7% in FY2009 to over 18% in FY2016. For FY2017, a significant number of cities that normally are counted in the Merritt data base have not yet been reported, yet the ratio is on a path towards 19% share of all expenses. This ratio is similar to another commonly used denominator that incorporates the consolidation of all governmental funds (using the fund accounting modified basis approach). The main difference in using all “governmental funds” rather than “governmental activities” is that the former method uses a modified accrual accounting approach, while the latter approach uses an accrual basis that includes the recognition of infrastructure and total long term liabilities. In numbers, the median fixed cost share for all 2016 cities was less than a 1% differential, mostly related to the absence of expense for depreciation and amortization.

Lastly, the ratio involving all primary governmental expenses encompasses an even broader measure of all governmental spending and potential resources to account for and pay pensions. Whenever a city operates an enterprise operation like an electric utility, water & sewer enterprise, or an airport these activities employ city workers that are usually participants in a municipal retirement program. In turn, city contributions to pensions and OPEBs are often paid from local taxes and general revenues rather than customer charges applying to these users of airports, utilities, and other enterprise activities. A proper economic allocation of cost should require user fees to be based on applying a pro rata share of the costs of service-specific municipal employees participating in a retirement plan. This ensures that the true costs of compensating these employees are being paid by the residents who benefit from their work, rather than pushing those costs onto future generations. Using this approach, fixed costs of governmental long term liabilities (excluding enterprise debt) is the least burdensome at around 13.5 percent, but it is only meaningful if governments properly charge users of the municipal enterprises for their appropriate economic cost of workers engaged in these “business” pursuits.

At what point are fixed costs likely to cause fiscal stress depends on a host of factors starting with the wealth and resources of the community and their ability to increase taxes, fees or other charges to avoid cuts to basic services, especially related to the health and safety of its residents. When the city of Detroit filed bankruptcy in June 2013, current debt service, pension contributions, and OPEB amounted to 53.9% of the general fund and 31.3% of total governmental activities expenses.

by Richard Ciccarone