by Richard A. Ciccarone

When a municipal government suffers severe fiscal problems, be it a city, county, school district, utility district, or any other special purpose government, those problems have a tendency to impact or be shared by other governments. Bond markets identify this interconnectivity, and apply broad brushes discounting borrowers sharing common elements with the troubled municipality.

New York City was the center of municipal finance attention for nearly a decade after defaulting on its notes in 1975. It was identified at the time that, while the City suffered serious financial mismanagement issues, a significant factor stemming its struggles related to overall economic and demographic base declines common in other industrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest. This led to not only the City government itself receiving a borrowing penalty, but it prompted a “guilt by association” penalty for not only other credits sharing the same overlapping tax jurisdiction; but, also to other places with similar geographic and socio-economic characteristics as well. These penalties were not completely resolved until the general economic recovery of the area in the 1990s.

The market was correct to generalize the credit risk clusters associated with older Rustbelt cities, as central cities such as Detroit, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland, among others, suffered serious financial challenges in subsequent decades. The credit cluster among these cities was shared characteristics of economic base, and base diversity and maturity, rather than a geographic cluster.

The starting point for state and local cluster concentration is common geographic and economic interplay. However, unique characteristics of individual governments can compound or mitigate these forces.

Other generalizable municipal credit clusters include natural resource-based economies, and troubled pension and OPEB funds. Additionally, the Washington Public Power Supply (WPPSS) default in 1983 created cluster risk around public power authorities that use nuclear power with heavy debt loads.

There are two primary topics that need to be addressed. First, what are the key issues that increase the chances for intergovernmental cluster risk? Second, what are some current potential candidates?

Intergovernmental Relations

The starting point for state and local cluster concentration is common geographic and economic interplay. However, unique characteristics of individual governments can compound or mitigate these forces.

Weak state financial condition normally leads to declining support for local governments. State laws limiting revenue flexibility and promoting or allowing poor financial management can have negative effects. Conversely, political cultures that support good government and co-operation between governmental units and intervention when there is trouble are better able to handle distressed situations.

States can cut back appropriations, mandate increased spending by local governments or otherwise make unfunded mandates. States can also make statutory changes limiting local government taxing powers, or redirect funds back to state governments. State willingness to intervene can often be a positive. However, when cluster contagion occurs, and multiple local units of government need assistance simultaneously, it can create a significant burden even on states with healthy financial positions.

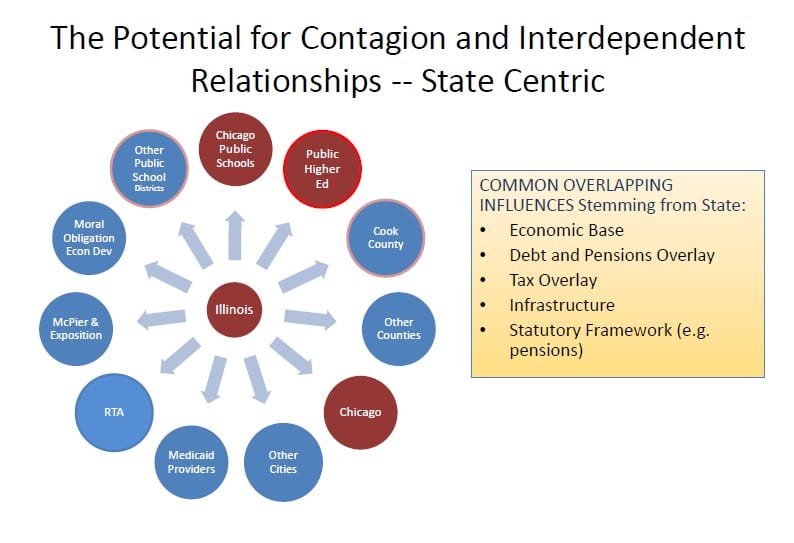

State Centric Perspective

Since local governments are subdivisions of state sovereignty, the state grants them powers to enact laws, collect taxes, issue debt and administer responsibilities from the state. Although a state authorizes local governments to act on its behalf, it retains ultimate responsibility for maintaining the health, safety and welfare responsibilities for all its citizens, if the local government is unable or unwilling to do so. In so doing, states normally share the costs in varying degrees with local governments to provide support for issues involving socio-economic fairness and statewide growth. Public education and health care for the indigent are the most common responsibilities that states share the financial burden with local governments.

The state’s own financial health can affect the amount and degree to which it is able to fund and allay the cost of local governance. A downturn in state tax revenues or rise in costs for operations or to pay its debts often spells trouble for local governments burdened by their own liabilities.

Local Centric Perspective

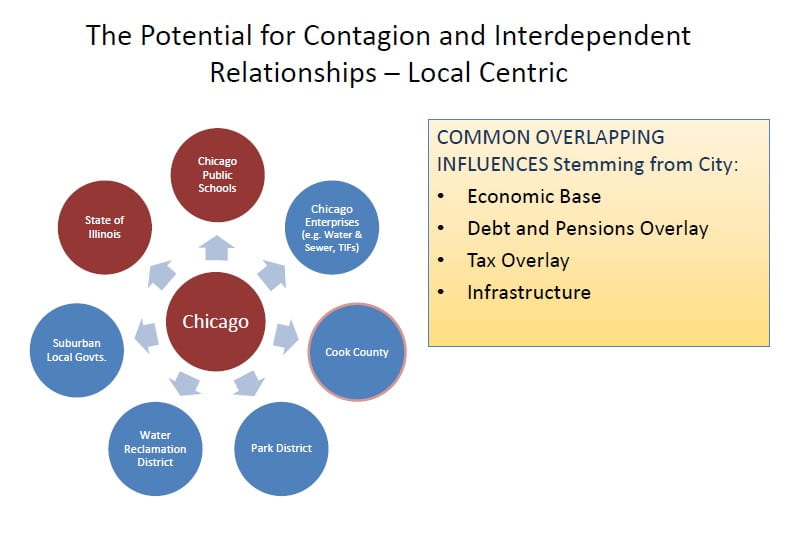

At the local level, the potential for contagion due to intertwined and interdependent relationships threatens to spill over into overlapping and adjacent governments, apart from whatever is going on at the state level.

At the core, the strength and resilience of an area’s economic base provides the foundation for an area’s penchant for local cluster risk. Growing local economies are more resistant but not immune to the spread of fiscal contagion to overlapping or nearby governmental units.

Dramatically higher taxes to cover an overhang of debt can affect local and regional attractiveness. Local fiscal policy that has gone awry can jeopardize the health of the metropolitan area if affordability, quality of life, adequate public facilities, and land development and transportation networks are adversely impacted. This is especially true when the main culprit triggering the negative trend emanates from the primary commercial or population centers in the area.

Common Elements of Local Cluster and Contagion Risk

- Negative Population Trends

- High Overlapping Debt and Pension Liabilities Per Capita

- Taxing Capacity – Both Ability and Willingness to Pay

- Deferred Infrastructure Improvements

There are also other secondary symptomatic factors which may signal that cluster risk might be festering, such as median household income, the median age of a county’s housing stock and the overall condition of the central city’s unrestricted net position relative to the size of the city’s total governmental expenditures.

Illinois and Chicago as Examples of State and Local Cluster Risk

Illinois is a prime example of cluster risk at work. Its chronic failure to maintain adequate appropriations to fund its public pensions on an actuarial basis has left the state with a huge budget gap to cover escalating pension costs. The state’s constitutional protection clause that prohibits the diminishment of pension payments to workers, upheld by the State Supreme Court, appears to have left the state in a highly difficult position to close the gap without dramatically raising taxes or reducing services. The severity of the burden has left state leaders with differences on the need for serious reforms and in conflict as how to solve the issue. The net impact has resulted in a deadlocked legislative and executive standoff with no state budget approved for the entire 2016 fiscal year. This unusual situation has resulted in substantial de facto cutbacks to departments or programs that didn’t receive protection either under a Court order, automatic appropriation protection or a legislative consent decree. Throughout the standoff, public universities, state aid educational appropriations and social service funding were among the spending needs that were most affected. At the same time, an urgent request for additional support from Chicago governments, including the Chicago Public Schools, has fallen short of its needs. The state’s own credit distress has led to numerous credit downgrades by the rating agencies and higher borrowing costs for state agencies and local government borrowers. (A temporary budget fix is still ongoing for the first half of FY 2017).

For these reasons, Illinois is probably the current headline epicenter of cluster and contagion risk among the fifty states. The situation is exponentially compounded by co-incident major fiscal challenges that currently exist in the City of Chicago and the Chicago Public Schools. At both the state and local levels, the root issue of the Illinois problem emanates from its long time failure to adequately address its underfunded public pension funds. Illinois’s economy, tax base and debt levels are so interconnected with Chicago that it is highly difficult to isolate the fiscal problems that exist for taxpayers in the Prairie State. Recent fiscal shortfalls have had an adverse waterfall effect on a number of associated state agencies and many local units.

In Chicago’s case, the combination of overlapping debt and pension liabilities is at the heart of the cluster crisis.

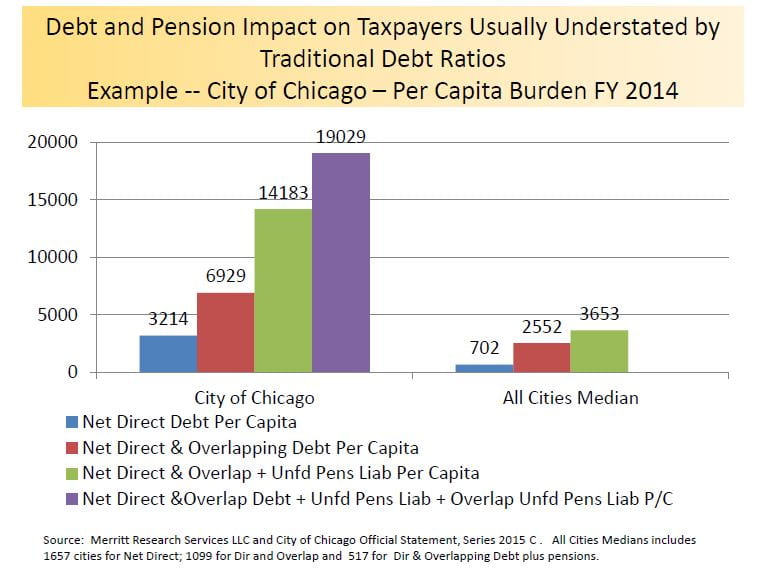

In the municipal credit analysis world, the traditional analytical approach to compare overlapping debt ratios is based on the inclusion of a city’s own direct debt plus the proportionate share of the overlapping indebtedness that pertains to the assessed tax base of the government being analyzed. A broader approach that has become increasingly popular among analysts expands the numerator to include the direct unfunded pension liability into the debt ratio equation. The rationale for doing so is that even though the unfunded pension liability fluctuates year to year due to actuarial assumption variances such as market valuation and contribution considerations, the pension liability is still a fairly immutable form of indebtedness that weighs on taxpayers for years to come.

What is missing from a true long term indebtedness burden to a city is the total proportionate share of overlapping unfunded pension liabilities that must be borne by taxpayers. For example, Chicago’s taxpayers must pay their share of the unfunded liability that applies to all five of the city’s pension funds as well as all or a portion of the unfunded liabilities that are related to its overlapping governmental units (i.e. Chicago Public Schools, Cook County, Greater Chicago Water Reclamation, Chicago Park District and the Cook County Forest Preserve). Since the overlapping pension liabilities are not available in the official financial documents of any one governmental entity, it is necessary to manually calculate the proportionate share in order to have an appropriate total indebtedness number to use against traditional burden comparability ratios against population and the full market taxable value of property in the city.

The overlapping burden effect of its legacy pension and outstanding debt, involving multiple governmental units, creates a consolidated burden on the same Chicago taxpayers. Using financial data applying to FY 2014, the combined effect of adding each Chicago jurisdiction’s debt and unfunded liabilities, the city’s taxpayers were on the hook for $32.4 billion in unfunded liability, which is nearly double from the $19.8 billion that would apply only to the city’s direct load. This number excludes the city’s proportionate liability for the huge state unfunded liabilities.

Moreover, by adding the proportional overlapping pension liabilities to the traditional debt ratios used by municipal credit analysts to compare one city to another, Chicago’s indebtedness stands out well above the medians for all cities as compiled by Merritt Research relative to its population and the full taxable value of its property tax base by all levels of comparison. These consolidated levels likely were not calculated for FY 2015; however, if they were, the burden would likely have appeared worse since the city’s pension assumption blended discount rate was lowered under Governmental Accounting Standards Board rules, creating an even larger liability. (Editor’s note: Interested readers would be well advised to read the author’s complete article on Credit Cluster and Contagion Risk Related to Distressed Municipalities (see reference below) to better understand cluster impact dynamics, including the impact on Illinois and Chicago.)

The Model:

Below are two useful models, one focusing on states using Illinois as an example, and the other using Chicago to focus on local characteristics, showing the types of entities and common elements of risk cluster and financial contagion.

Identifying At-Risk Areas

Following these models, cities deemed most at risk for cluster and contagion include Chicago, New Orleans, Detroit, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh,, Syracuse, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Birmingham. For more information on how these models were developed, details on the individual elements as well as the individual cities identified as being at higher risk, and other elaborations on the subject matter in this article, please see Richard Ciccarone’s paper, “Credit Cluster and Contagion Risk Related to Distressed Municipalities.” This paper was presented at the 5th Annual Municipal Finance Conference, held by The Brookings Institution’s Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, Brandeis International Business School’s Rosenberg Institute of Global Finance, and the Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis, in July 2016.

Richard A. Ciccarone, President & CEO of Merritt Research Services, LLC and Co-Publisher of MuniNet Guide