More on 2015 City Pension Funds:

This is Part II in Richard Ciccarone’s look at city pension funds in 2015 and the future landscape. Part I can be found here.

Earlier this month, MuniNet reported that most city pension plan funding ratios took a positive bounce based on results found in 2015 city audit reports. We cited the elimination of asset valuation multi-year smoothing, the relative improvement investment returns going into the year and a sprinkling of pension reforms as the primary reasons for improvements. That’s the good news; but, there is another side of the picture that needs to be considered. The elimination of asset value smoothing means that funding ratios are much more volatile than they have been in the past. While the simple explanation for sharper movements in pension funding conditions is tied to the elimination of asset valuation smoothing, the longer term outcome for funding adequacy relies heavily on the capability of investment returns to keep up with the high bar set by hopeful discount rates (i.e. investment return) embedded into most public pension plans.

Since public pension asset valuations reported in a government’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) often apply to the pension plan’s measurement period that took place in the previous fiscal year, many FY 2016 audits will be capturing into their equations the results of the weak stock and bond market that transpired in 2015. So, it should come as no surprise public pension funding ratios will likely be down when next year’s funding ratios are compiled.

A number of recent articles and reports have discussed the immediate and long term challenges posed to public pension plans that continue to rely on relatively high discount rates (i.e. investment return) assumptions to determine the funding status of their plans. High investment return assumptions year-over-year require less taxing public or employee dollar contributions to fund a pension plan over the long term since higher expected earnings are anticipated to accumulate over to time to pay benefits. Unlike the corporate sector which usually uses a long-term average of high quality corporate bonds as their funding rate (discount rate) assumption (the permissible rate this year is about 6%), many public plans have historically projected earnings targets that are intended to mimic historical asset allocation returns over the past 50 years. Consequently, the average discount rate used by public pension funds closer often hovered near 8%. For a variety of reasons, including the economic adjustments that followed the credit crisis, the outlook for both stock and bond investment returns is far less optimistic. That’s caused some plans to rethink their “discounts”, albeit gradually, by lowering their investment return assumption.

The ability to reach higher investment return targets appears to be a tall order that requires a lot of faith in optimistic conditions for long term investment results.

Using data from FY 2015 city CAFRs, compiled by Merritt Research Services, LLC on over 1400 single and agent city pension plans, the average 2015 city pension plan discount rate stands at 7.21% and the median at 7.5%. Public pension discount rates have been tweaking down over the past few years as a number of cities have modestly lowered their assumptions by ¼% to ½%. As a caveat, the Governmental Accounting Standards Board’s (GASB) new rules for public pensions, effective for reporting in 2015, provided a platform to apply a more rigorous discount rate if the plan’s actuarially projected that benefits would outstrip the amount of monies available to pay claims sometime in the future. According to GASB 67 & 68, when such a crossover point does occur, then that plan has to use a lower discount rate equal to a 20-year tax-exempt municipal bond index for the portion of the obligation in which assets are insufficient to cover. So far, the lower discount rate impact has only been applied to relatively narrow base of public pension funds. One reason that governments have been able to avoid breaking the “crossover point” is that they have the right to extend the pension expense amortization time that they use to make contributions. By doing so, they can defer near term cash contributions to fund the plan and effectively transfer a larger share of the burden to future taxpayers. Chicago’s recent proposal to reform is an example of one of the more extreme deferrals as its large unfunded Municipal Employers preliminary schedule calls for the plan to be 90% funded by 2057. By that time, most of the retirees receiving pensions will have already passed away.

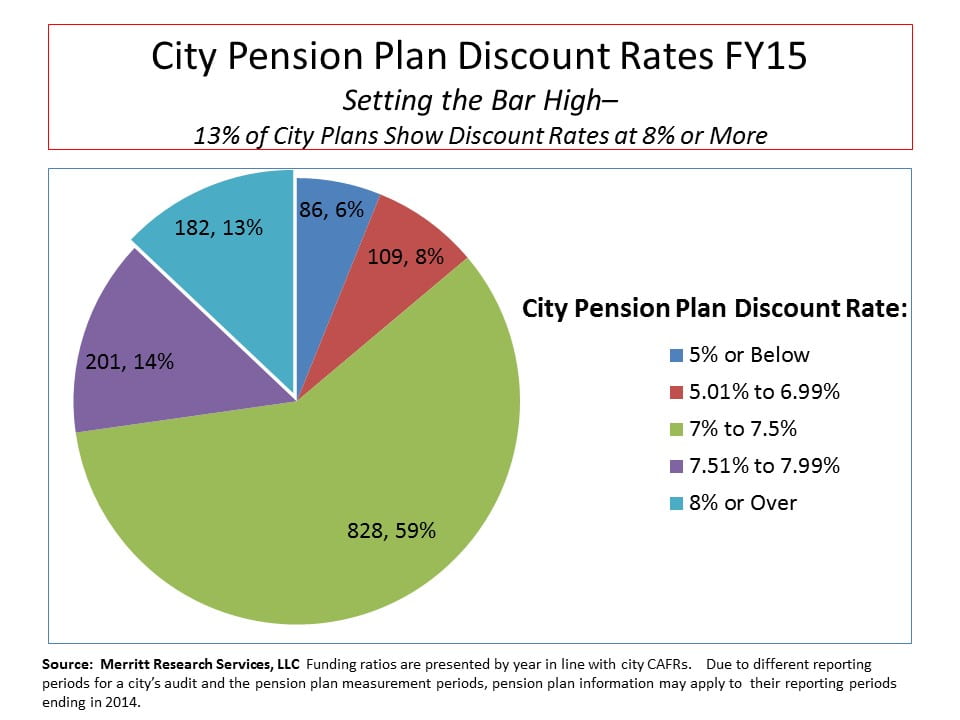

The ability to reach higher investment return targets appears to be a tall order that requires a lot of faith in optimistic conditions for long term investment results. According to Merritt Research data, out of the 1406 cities in their sample study, thirteen percent (13%) of the city plans are counting on an investment return discount rate of 8% or more (see pie chart below). Another 14% believe that they can achieve returns in the range of 7.5% to 8%. The vast majority of the plans (59%) are in the 7% to 7.5% range. In the more conservative camp, 8% of all city plans have set the bar at a more attainable target investment return assumption of between 5% and 7%. Finally, the remaining six percent of the plans use either a determined or GASB directed blended discount rate that falls below 5%. A number of those plans, in the last category are required to use a blended rate that incorporates a tax-exempt municipal bond rate for at least a portion of the projected return assumption under the GASB rules because of their weak funding status.

While the number of city pension funds with 8% or more annual discount rates has edged downward in recent years, there is still a fair share of cities that are still hanging on to the high target rate. Albany, GA and Houston, TX stand out among cities with populations over 50,000 with at least one of their pension funds reaching for 8.5% returns. Albany’s 2015 funded ratio stood at 70.1% with $50.6 million in unfunded liabilities. However, if its discount rate was adjusted by 1% to 7.5%, its unfunded liability would increase by 33% to $68.1 million. Houston, TX’s Firefighters fund looks fairly well funded based on its most recent audit as it shows an 87% funding ratio at the end of the city’s fiscal year (June 30, 2015). But, if the Houston plan reduced its discount rate of 7.5% by 1%, analysis, its 2015 funding ratio would have slipped to 79.7%, still not bad for public pensions. Nevertheless, the Houston Firefighters plan reported that its actual rate of return for 2015 was only 1.28%. While that return applies only to a single year in the market, that’s still a long way from 7.5%, no less 8.5%.

Other example cities with discount rates of over 8% include Gainesville, FL (2 plans at 8.3%); Waltham, MA (8.25%); Somerville, MA (8.25%); and Providence, RI (8.25%) (See accompanying table).

The city of Dallas presents an interesting case involving a dramatic sea change in its earnings expectations. Its two largest pension plans ranked among the highest investment return assumptions of all cities until only recently. In their 2014 measurement period, the Employees Retirement Fund of Dallas applied the GASB blended discount rate from 8% to 5.76%, only to be outdone by the Dallas Police & Fire Pension Systems which also determined that it needed to incorporate the blended rate. The net impact meant that city’s effective discount rate fell from 8.5% to 4.54% and then again in 2015 to 3.95%. The sharp reversals were prompted by a more negative outlook for investment performance in the coming years as well as revaluation of real estate and private equity assets. The degree to which Dallas’ lowered its discount rates is what raised eyebrows. The reduced discounts rates caused the both plans’ funded ratios for 2015 to drop precipitously with the Employees Retirement Fund of Dallas reduced from 84.9% to 59.7% and the Police & Fire Fund from 38% to 28%.

Predicting market performance based on recent market performance is a dangerous proposition to determining long term performance. In light of well-deserved focus on public pension funding, close inspection of annual investment experience is not surprising or unjustified. As long as actual rates of return for public pension funds fall short of hopeful targets, there will be plenty of second guessing of discount rates.

If the market strings together a two or three listless total investment return years together, there will be plenty of political pressure on more city pension funds to bite the bullet on discount rates, cough up more money from taxpayers, squeeze out existing services or intensify the call for more significant pension reforms.

Richard A. Ciccarone is a Co-Publisher of MuniNet Guide. He is also President and Chief Executive Officer of Merritt Research Services, a municipal bond credit database and research company that primarily serves institutional investors, investment dealers and bankers. Mr. Ciccarone has over 35 years of investment management and research experience, specializing in municipal bonds.