by Peter Stettler

Over the past ten to 15 years the major domestic network airlines have relied on regional airline partners to efficiently serve smaller and mid-sized airports across the nation. Lately the advantages of the regional airline model have begun to wane due to the surge in fuel prices, consolidation of the domestic airline industry and realignment of airline networks, and regulatory changes that have created an imbalance in the supply and demand for entry level pilots. As a result, the share of domestic capacity provided by regional carriers declined from 2010 through 2015 after experiencing a decade of significant growth. Republic Airways Holdings (Republic or the company), the second largest provider of regional jet operations to the major airlines, is in the midst of a significant reorganization stemming from these dynamics that may be a harbinger of changes in the regional airline industry that could have implications for small and mid-sized airports of which municipal bond analysts and investors should be aware.

The Regional Model

Republic is one of several providers operating regional jet service for the major domestic airlines (the majors) under their regional brands: US Airways Express and American Eagle in the case of American Airlines (American); Delta Connection for Delta Air Lines (Delta); and United Express for United Airlines (United). The other regional aircraft providers (the regionals) currently include SkyWest, Inc., Mesa Airlines, Inc. and Trans States Holdings, Inc. as well as American’s wholly-owned subsidiaries Envoy, PSA Airlines and Piedmont Airlines, and Delta’s wholly-owned subsidiary Endeavor Air[1].

The regionals operate under fixed-fee capacity purchase agreements with the majors (i.e. the regional provides a plane and crew in return for a fixed-fee to operate a route). Under these agreements the regional airline is responsible for the costs of labor (crew), aircraft maintenance, safety and compliance oversight, and aircraft financing. The major carrier retains responsibility for ground support and gate access; incurs the operating expenses related to fuel, navigation, airport use, and terminal handling; and determines pricing, scheduling, ticketing, and seat inventory. Competition among the regionals is fierce, with price to the major airline being the determining factor in the award of most contracts, resulting in slim operating margins for the regionals.

The Growth of the Regionals

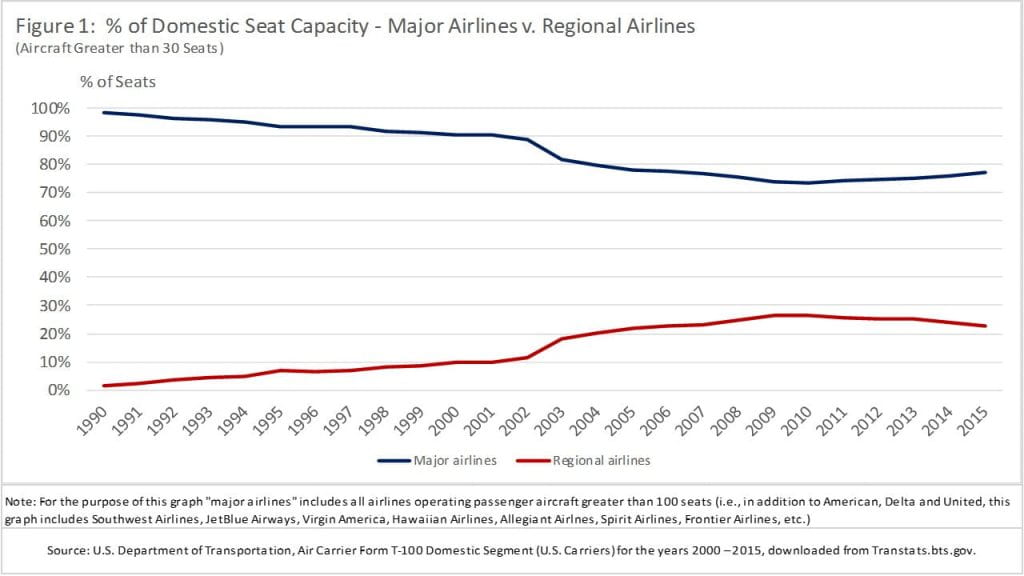

The original regional airlines primarily provided turboprop services linking smaller airports to larger cities and network transfer hubs. As of 1990, aircraft of between 30 and 50 seats accounted for just 1.6% of total seat capacity provided by all aircraft of more than 30-seats based on data from the US Department of Transportation[2]. (Figure 1)

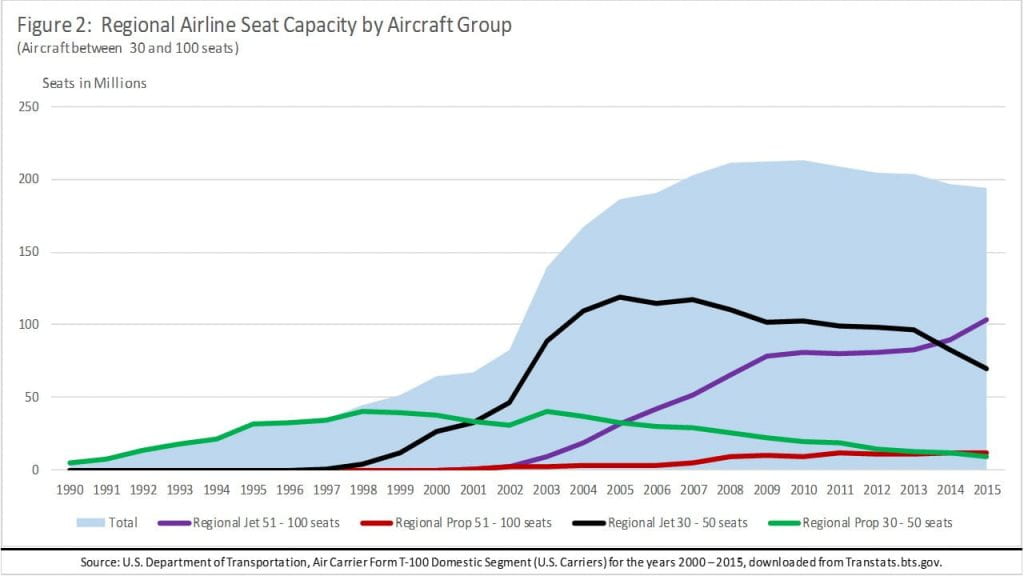

By 1997, the regional carriers had grown to almost 7% of the market but were still focused on operating 30 to 50 seat turboprops. The industry began to take on greater importance with the introduction of the 50-seat regional jet in 1997, which passengers favored over turboprop aircraft, with the regional share of the market reaching 9.8% of total seat capacity in 2000. (Figure 2)

The importance of the regionals surged in the early 2000s following the events of September 11, 2001 and the subsequent national economic recession, as well as the introduction of larger, more efficient regional aircraft of up to 100 seats 2001. In light of the financial pressure placed on the major domestic airlines as a result of reduced passenger demand, the majors sought to reduce costs by outsourcing service to small and medium-sized airports, as well as some frequencies to major markets, to the regionals that were able to offer favorable contracts due in part to lower costs under their labor agreements. By 2003, aircraft of between 30 and 100 seats accounted for 18.2% of the market and rose to 23.2% in 2007 when total domestic capacity peaked at 873.9 million seats.

Changing Dynamics of the Regional Industry and the Effect on Airports

While the regional share of the market continued to increase through 2010, the dramatic increase in oil prices and the economic recession of 2008-2009 began to erode the benefits of the regional model. In particular, 50-seat jet aircraft began to fall out of favor due to unfavorable economics, as the rise in fuel prices significantly increased their operating costs on a per passenger basis, as well as growing passenger disenchantment with the smaller jets which were developed from business aircraft designs. As a result, 50-seat and smaller regional jets began to leave airline fleets, replaced with larger regional jets that have better operating economics and offer greater passenger comfort as they were designed for commercial service. Furthermore, the consolidation among the major airlines fostered the realignment of their networks with an increased focus on their larger network hubs and the greater utilization of their own aircraft at the expense of regional aircraft. As a result, the regional carriers’ share of the market declined to 22.7% of total seat capacity by 2015.

The changes in network strategies and the declining market share of the regional carriers also affected the service levels at the nation’s airports, with larger airports benefiting while medium and small airports overall have seen passenger activity remain stagnant or decline. Based on FAA data for the 151 airports that achieved “hub” status[3] in at least one year between 2001 and 2014 (Appendix 1), the total number of enplaned passengers using these facilities peaked at 740.9 million in 2007.[4] (Figure 3) The economic recession of 2008 led to a decline of 8.6% in passenger volume at these 151 airports for the two-year period ending in 2009. (Figure 4) Medium hubs experienced the greatest decline at 15.0%, followed by small hubs with a decline of 11.1%, and large hubs which saw traffic fall by 6.6%.

As the national economy began to expand after 2009, passenger volume rebounded strongly, recording an 8.9% overall gain from 2009 through 2014. However, the recovery among airports was uneven, with large hubs accounting for almost all of the gains with an overall increase of 12.2% for the five-year period. Large hubs represent the only category that has exceeded 2007 passenger levels. In comparison, passenger volume at medium hubs increased just 2.4% between 2009 and 2014, and remains 12.9% below 2007 levels, while small hubs experienced a further decline of 2.9% from between 2009 and 2014.

Among the airports that experienced the largest declines in passenger volume in the post-recession period were secondary network hubs. (Figure 5). Cincinnati / Northern Kentucky International Airport experienced a decline of 44.6% between 2009 and 2014, while Memphis International Airport recorded a decline of 64.4%, as Delta significantly reduced connecting operations that primarily utilized regional jets at these airports. Delta’s actions reflect the carrier’s decision to focus operations on its larger network hubs, particularly Atlanta Hartsfield-Jackson and Detroit Metropolitan airports, as it absorbed the operations of merger partner Northwest Airlines into its system, as well as its decision to shutter its wholly-owned regional carrier Comair, whose cost structure was no longer competitive with the other regionals.

A third smaller network hub airport, Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, experienced a 21.6% decline as United eliminated its connecting operations due, in part, to the growing staffing difficulties at its regional operators that provided most of the service at the airport. United shifted the connecting traffic over its other hubs, primarily through Chicago O’Hare and Newark Liberty airports.

Secondary network hubs were not the only airports to see significant declines. Five other medium hubs – Albuquerque International Sunport, Bob Hope Airport (Burbank, California), Ontario International Airport (California), Milwaukee General Mitchell International and Buffalo Niagara International – and 23 small hubs reported declines of more than 10% between 2009 and 2014. However, six medium hubs reported gains of more than 20%, four of which are large Southwest Airlines stations, led by Houston Hobby which grew 41.9% for the period, while five small hub airports recorded gains of more than 50%, led by Mesa Gateway which received its first significant commercial service in 2010.

Among the large hubs, only Washington Dulles International and Philadelphia International airports experienced declines in passenger volume between 2009 and 2014, with Dulles declining by 6.4% and Philadelphia a modest 1.4%. In contrast eight large hubs recorded gains of more than 20% over the period, led by Charlotte Douglas International with an increase of 25.5%.

Increasing Regulatory Burden Hampers Regional Carriers

While the recent decline in fuel prices has eased the economic pressures on the regional jet fleet, several factors continue to spur airlines to move to larger aircraft. Chief among these reasons are traditional factors such as long-term economic considerations, passenger preference, and network needs. However, a combination of regulatory factors is driving both an increased demand for, and a reduced supply of, entry level pilots at the regionals, leading to staffing challenges and pressure to raise entry level pilot wages at the regionals, which are now the largest source of pilots for the nation’s major airlines.

Two of the regulatory factors affect the airlines’ demand for pilots – the federal mandatory retirement age for pilots and recently enacted limits on pilot duty time and the hours a pilot may fly. The federal mandatory retirement age for pilots had long been set at 60, but was raised to age 65 in 2007 providing the major airlines a 5-year reprieve to the loss of a significant portion of its pilot workforce. However, beginning in 2012 the pace of forced pilot retirements began accelerating as an increasing number of pilots reached the age of 65 at the major carriers. As the majors recruit pilots from the regional ranks, the flow of pilots from the regionals to the majors has increased in parallel, increasing pressure on the regionals to recruit and train entry level pilots to maintain their staffing levels.

The second regulatory factor affecting the demand side of the equation is the implementation of the Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act of 2010 (FAA Act of 2010) that placed limits on duty time and the hours a pilot may fly, as well as mandating rest periods between shifts, to address safety concerns related to pilot fatigue. However, these changes also force U.S. based commercial airlines to maintain larger pilot staffs to sustain the same level of service offered prior to the new regulations. Based on data from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) the mandatory retirement age and the new anti-fatigue safety requirements, combined with anticipated airline growth, are expected to generate demand for an average of 1,900 to 4,500 new commercial pilots annually over the next 10 years (the GAO Report).[5]

While the regulatory pressures on the demand side are significant, the change that may have the greater impact on the regional carriers is on the supply side of the equation – the 2014 implementation of the FAA Act of 2010 requirement that all commercial airline pilots hold an air transport pilot certificate. Prior to this change, airlines were able to hire as entry level first officers pilots that held a commercial pilot certificate, which requires a minimum of 250 hours of flight time among other conditions to obtain. An air transport pilot certificate, in comparison, requires a minimum of 1,500 hours of flight time, along with additional training requirements. The overnight need to gain an additional 1,250 hours of flight time had the immediate effect of both eliminating a significant number of previously qualified pilots the regionals could hire while drastically increasing the costs and length of time required for prospective pilots to attain the necessary certification.

The GAO report indicates that academic education and flight training at a 4-year aviation degree program necessary to obtain a commercial pilot certificate can cost well in excess of $100,000.[6] Candidates must then find a means to gain the necessary flight time and pass additional certification testing to obtain the air transport pilot certificate, which adds another two to four years and tens of thousands of dollars in costs before a candidate becomes eligible to apply for an entry level position at a commercial airline. Faced with these growing costs that prospective pilots must finance on their own, the long lead time to employment, and the low entry wages offered at the regional carriers, many aspiring pilots no longer view pursuing a career in aviation as being viable, resulting in a decreased supply of candidates for the regionals to consider.

Republic Files for Bankruptcy

While all of the regional carriers are facing challenges brought about by the economic and regulatory conditions confronting the industry, the gravity of the situation at Republic was magnified due to the company’s protracted negotiations with its pilots’ union for a new labor agreement over the past eight years. The pilot’s contract first became amendable in 2007, which coincided with the beginning of a national economic recession that fostered a difficult negotiating environment as passenger traffic, and thus airline revenues, began to decline while the pilots sought increased wages and improved work rules. While the parties reached tentative agreements on several points by 2009, the national union’s decision to put the Republic local into trusteeship for the failure to maintain proper financial controls further complicated the situation. The company and the pilots’ union finally reached an agreement in October 2015, but the inferiority of Republic’s labor contract compared to its competitors over the previous seven years led to significant pilot attrition and compromised the company’s ability to recruit replacement pilots. As a result, Republic grounded significant portions of its fleet, eventually leading Delta to file suit alleging Republic was not meeting the minimum flying levels under its capacity agreements and thus in violation of its contracts.

While the new labor agreement allows the company to compete on equal terms for entry level pilots, the need to recruit and train a sufficient number of pilots to restore full operations requires time. Also, the increased costs of the new labor agreement suggest the revenues generated under the capacity agreements with the majors may no longer cover the company’s expenses. Republic approached its major airline partners in an attempt to renegotiate its contracts, which the majors resisted. With the carrier finding it increasingly difficult to meet its contractual capacity obligations, confronting the Delta lawsuit, and facing increasing financial pressure stemming from the new pilot’s agreement and inadequate compensation under its capacity agreements, Republic decided to file for protection under Chapter 11 of the US Bankruptcy Code (Chapter 11) on February 25, 2016.

At the time of the bankruptcy filing, Republic operated approximately 1,000 daily flights to 105 cities in 35 states, with 510 flights operated for American as US Airways Express and American Eagle; 240 flights operated for Delta as Delta Connection, and 280 flights operated for United as United Express.[7] Raymond James estimates that Republic accounts for approximately 20% of American’s regional capacity, 15% of Delta’s regional capacity, and 11% of United’s regional capacity operated with a fleet comprised of 41 Embraer ERJ-145 regional jets (50-seats), 178 Embraer EMB-170/175 regional jets (70/75 seats), and 20 Bombardier Q400 turboprops (75 seats).[8]

Through the Chapter 11 process Republic is seeking to modify the agreements with its major airline partners to bring them in alignment with its fleet, staffing and cost structure; simplify its fleet and operations by eliminating out of favor 50-seat jet and turboprop aircraft to focus on one type of aircraft (EMB170/175) to reduce maintenance and training costs; place all of its operations under a single operating certificate (subsidiary) to gain efficiencies; and to secure additional liquidity to fund future operations and growth.

Whether or not Republic will be successful in obtaining these goals and emerge from the Chapter 11 proceedings is uncertain at this time. Should the company be forced into liquidation, the pressure on the remaining regional carriers may temporarily abate due to reduced competition and the availability of Republic’s qualified pilots to address staffing shortages. However, it may take time for the other regional carriers to acquire and certify enough aircraft, as well as hire and train a sufficient number of pilots, to absorb the flying currently undertaken by Republic. Should Republic be successful in reaching new agreements with the majors and emerge from the bankruptcy proceedings, the status quo will likely hold for the short-term.

Whatever the outcome of the Republic bankruptcy, the growing imbalance between supply and demand for entry level pilots affects the entire industry. As a result, domestic airlines are likely to face rising costs in the form of both training programs and entry level wages to attract a sufficient pool of candidates to maintain service levels. To balance these costs, the airlines are likely employ strategies to gain economic efficiencies, such as continuing the shift away from 50-seat jets to larger regional or mainline aircraft and, where possible, increase air fares. Small and mid-sized airports thus remain vulnerable to adjustment in service levels, whether it be a reduction in frequency, capacity, or the elimination of service where demand is not sufficient to support the use of larger aircraft. Particularly vulnerable are airports in close proximity to other facilities where the airlines could consolidate service to serve a region, or within a reasonable drive of larger airports with already high levels of service. A reduction or loss of service may affect airport revenue generation and the related ability to service obligations, including debt service. On the other hand, airports that sustain service may experience increased capital costs should current facilities need to be remodeled to accommodate larger aircraft. While larger airports gain from the renewed financial strength of the major carriers, analysts and municipal bond investors should pay attention to developments at the regional carriers and how the majors adjust service to small- and mid-sized markets and how these adjustments affect the cash flow and capital needs, and the related debt payments, of smaller airports.

[1] Republic operates through its two subsidiaries Republic Airways and Shuttle America; SkyWest, Inc. operates through its subsidiaries SkyWest Airlines and ExpressJet Airlines; and Trans States Holdings Inc., operates through its subsidiaries Compass Airlines, GoJet Airlines and Trans States Airlines. Previous regional operators include Atlantic Coast Airlines, Atlantic Southeast Airlines (now part of ExpressJet), and Delta’s wholly-owned subsidiary Comair.

[2] U.S. Department of Transportation, Air Carrier Form T-100 Domestic Segment (U.S. Carriers) for the years 2000 – 2015, downloaded from Transtats.bts.gov.

[3] The FAA defines a hub as having at least 0.05% of national enplanements, with small hubs serving between 0.05% and 0.25%, medium hubs between 0.25% and 1.0% and large hubs above 1% (for this report, the airports serving Guam and Saipan were excluded from the data)

[4] Passenger Boardings at Commercial Service Airports, Calendar Years 2000 – 2014; Federal Aviation Administration Air Carrier Activity Information System (ACAIS), downloaded from FAA.gov

[5] “Aviation Workforce: Current and Future Availability of Airline Pilots”, Government Accountability Office, February 2014

[6] IBID

[7] Source: “Declaration of Bryan K. Bedford Pursuant to Local Bankruptcy Rule 1007-2, In Re Republic Airways Holdings, Inc., et. al., United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District of New York, February 25, 2016

[8] “Airlines: Implications of RJET’s Bankruptcy Filing on AAL, DAL, SKYW, and UAL”, Raymond James & Associates, Inc., February 26, 2016.

Peter Stettler is President and Lead Analyst of Municipal Credit Analytic Services, LLC, an independent provider of credit research to municipal market participants. He may be reached at PeterStettler@MunicipalCreditAnalytics.com.

[table id=4 /]