Due to its lack of accounting for infrastructure assets and all long-term debt and liabilities, including pensions, general fund analysis has limited utility when analyzing municipal financial health.

By Richard A. Ciccarone

By incorporating the government-wide, net position concept introduced by the GASB’s Accounting Statement Rule 34 into their research, stakeholders can help investors, taxpayers, and government leaders better identify negative trends before they become financial crises.

The first four parts of this series on credit quality have concentrated on the several specific areas of financial condition, such as bond ratings, pensions, debt, OPEB, infrastructure and general fund operational cushions and liquidity. In this final installment of the series, we put it all together to evaluate the overall fiscal health of today’s U.S. cities.

Identifying a perfect bottom line ratio to compare cities is elusive for many reasons, not the least of which relates to the different ways that states and their sub-units are legally organized. For example, some cities are responsible for public schools, parks or fire services while others are not. When it comes to discussing financial condition, most analysts, observers and government officials have historically focused on the general fund since this is normally the largest and most discretionary in governmental fund accounting (discussed in Part Four of this series). While general fund analysis is important, its overemphasis can be prone to problems due not only to its short-term focus and the scope of what it covers. By design, it doesn’t encompass all of the funds that a government has at its disposal that might effectively provide relief for capital outlay or debt service or special services.

Relying solely on the general fund can also be problematic when comparing one government to another, especially when the governments are located in different states. An even bigger risk is that long-term debt liabilities, including large debts for pensions, are not accounted for in the general fund. That’s a big danger for those relying too heavily on the traditional measure of general operating condition to assess the potential for longer-term fiscal turbulence developing.

The best available accounting approach to putting together a comprehensive bottom line that encompasses the total picture of all resources and spending requirements is to incorporate the government-wide, net position concept that was introduced by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) when it implemented its Accounting Statement Rule 34 some 15 years ago. According to GASB’s Analyst’s Guide to Government Financial Statements, “The net position, simply stated, represents the resources a government has left to use for services after its debts are settled.”

Since GASB 34 made it possible to incorporate the net investment in infrastructure into the balance sheet, the net position in aggregate encompasses non-spendable assets as well. Since a portion of the net position may also be restricted and not available for public discretionary purposes, the amount of the net position that would be most relevant as a bottom line figure would be the unrestricted net assets portion. This amount is what the government has under its control, free and clear of all debts and restrictions. The net position can be isolated to cover governmental activities, business-type activities, like city utility enterprises, or a consolidation of the two types.

… a negative net asset position, especially one that is worsening, is frequently a sign that a government has taken on debt and liabilities that strain its ability to cover them.

The unrestricted net asset position number is the closest you will find on the balance sheet to the net worth of a corporation since it encompasses the entire spectrum of all government resources and liabilities, including infrastructure to unfunded retirement liabilities. Although it is probably underused and understated by analysts who inspect financial statements, the unrestricted net assets position usually provides a more revealing, longer range indicator of governmental condition than the simpler general fund balance.

Applying an Unrestricted Net Assets Ratio as a Comprehensive Financial Measure

Putting the unrestricted net assets number to its best use, Merritt Research introduced a new ratio in the early 2000s that compares the fiscal year end unrestricted net assets level against all governmental activities expenditures in order to place it into the context of the entity’s scale of financial responsibilities. When viewed in this way, the vast majority of cities are in positive bottom line territory with their available assets outnumbering liabilities. During the period 2006 through 2014, the median unrestricted net assets to governmental expenditures ratio fell from a peak of 29% in 2007 to a low point of 20% in 2011. The primary reason for the sharp decline was largely related to a burst of pension and other post-employment benefit unfunded liability adjustments coming onto the balance sheet. Also putting downward pressure on the bottom line for cities was sluggish infrastructure investment, as the depreciation expense outpaced capital outlays for repair, replacement and expansion over the past ten years.

During the past two fiscal years, most cities, but certainly not all, saw their bottom line position bounce back as measured by the unrestricted net assets ratio. With close to 1,200 cities reporting their GASB 34 fiscal year results for FY 2014, the net unrestricted assets ratio steadied at 22% of governmental expenditures, approximately the same level recorded for FY 2013. Although the recent stabilization in the net unrestricted position ratio provides some a modicum of good news, it’s not likely to last. We expect a significant deterioration in the net unrestricted assets ratio among most cities that have their own retirement and healthcare benefit plans. New governmental accounting rules under GASB 67 and 68, effective in 2015, call for the remaining portion of unfunded pension liabilities, which are not already showing up on the government-wide balance sheet, to take full effect. Further slippage will occur when financial statements begin to implement other new GASB Rules 73 and 74 dealing with Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEB), beginning after FY 2015.

The unrestricted net position number frequently appears on many city financial statements in negative territory for a wide variety of reasons. A negative net unrestricted number doesn’t necessarily mean that a government is insolvent or can’t pay its bills on a current basis. However, a negative net asset position, especially one that is worsening, is frequently a sign that a government has taken on debt and liabilities that strain its ability to cover them. Besides debt and pensions, it also covers unpaid bills, promises for worker benefits that have been accrued but not yet paid and the implicit write-off of infrastructure that may still be in use but is no longer carried on the books of a city as a viable asset. The unrestricted net asset number is imperative to look at on an absolute basis to determine why it is positive or negative as well as in relation to its trend.

In some cases, the number may be negative due to more benign risks to a government. For example, the State of Florida borrows to build new schools and pledges to repay this debt from state funds despite the fact that when it receives the proceeds from the bond issue, it donates the projects to the local school district. As a result, the state retains the debt on its books while the local school district picks up the asset. The downside of that transaction is that the holder of the debt cannot extract any future value from the “gifted” school building in the event, albeit unlikely, that it wished to sell the asset prior to the debt being paid off.

While nearly all states and cities have adopted the GASB rules for governmental accounting which provides for a net position number, there are exceptions. In a few states, like New Jersey, cities use a state statutory approach for financial presentations rather than incorporating the generally acceptable accounting practices associated with the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) Statement 34. That’s not only a problem for fair comparisons for investors and academics, but it also deprives taxpayers and citizens the opportunity to capture the accounting nuances from the broader reporting rules.

As we look for a bottom line number for cities, the net position and in particular, the unrestricted net assets, number has more of a holistic and more forward-looking tone than any traditional financial reporting number connected with governmental reporting. As long as governmental officials, taxpayers and investors learn and understand the importance and nuances of the net unrestricted assets numbers, they will have the capability to become more acutely aware of the financial challenges that a city faces and be able to take an appropriate course of action.

Looking for Patterns and Evidence that the Bottom Line Number Matters

The value of tracking the net position is already paying off for those looking to identify potential trouble spots. In our work, we have repeatedly found highly negative net unrestricted assets ratios among distressed cities, those which have contemplated or filed bankruptcy, defaulted, placed under state receivership or shown signs of chronic fiscal stress. There is little coincidence that some of the names of cities on the list of America’s most fiscally troubled also had a negative unrestricted net asset to governmental expenditure ratio. The ability to use this ratio as an early warning indicator is supported by the fact that Detroit’s appeared in negative territory in 2003 at -5.6% of governmental expenditures. Thereafter, the ratio worsened for each of the next ten years before it filed bankruptcy. By the end of Detroit’s FY 2012, the ratio hit a -97.9%. Similar negative tracking trends occurred for other cities that have been in the news relative to the seriousness of their financial troubles. Among others, they include Harrisburg, PA; Scranton, PA; Flint, MI; Pontiac, MI; Woonsocket, RI; Central Falls, RI; Stockton, CA and San Bernardino, CA.

… we have repeatedly found highly negative net unrestricted assets ratios among distressed cities, those which have contemplated or filed bankruptcy, defaulted, placed under state receivership or shown signs of chronic fiscal stress.

As mentioned earlier, a negative net unrestricted position ratio does not always mean that a city or government is facing an imminent fiscal crisis or one is that is inevitable. But negative numbers are certainly a shot across the bow that need to be cautiously examined to identify the cause and the trend of the imbalance.

Larger cities, especially older ones in economic decline from their heyday, are more likely to show negative net unrestricted asset ratios. Characteristically, they have more unionized work forces with legacy defined benefit programs that continued to weigh on the community even well after they shrank in population. The median net unrestricted assets to government expenditures ratio for the nation’s biggest cities (over 500,000 persons) shows a more troubling negative picture by falling from a positive 3.5% in 2007 to a recent low of -19.6% in 2014. The worsening trend is more significant to the municipal bond market because of the large amount of debt usually associated with the larger cities.

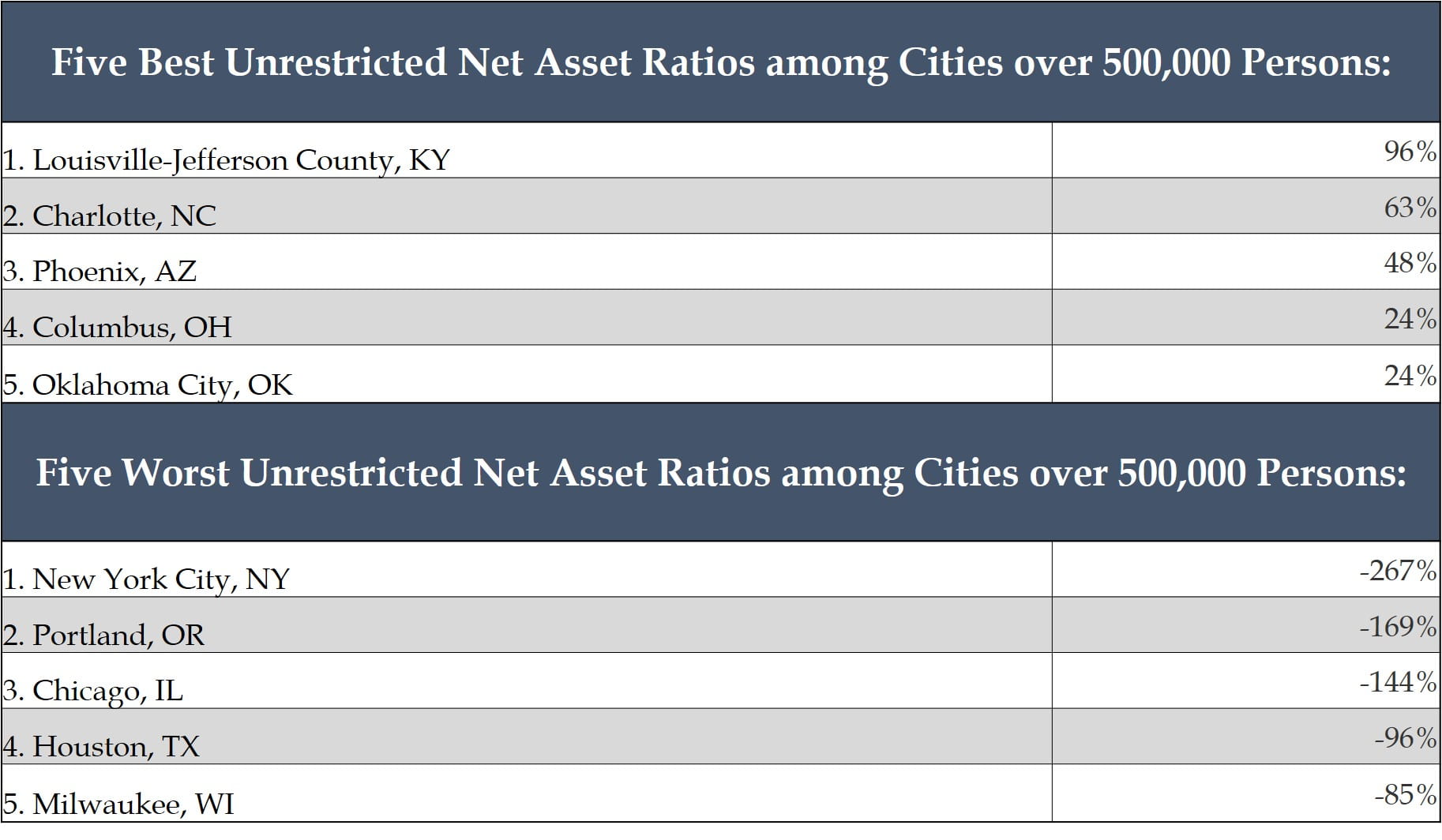

Out of the 32 of the 34 largest U.S. cities in the analysis, eleven have positive ratios. The five best and worst negative positions are as follows:

New York’s negative situation is a complex one but much of its adverse condition is due in large part to an aggressive reporting of its full OPEB liabilities as well as a significant portion of its single employer plan pension responsibility. The ratio worsened significantly in 2014 as the city became an early reporter under the new GASB 67 and 68 rules to account for the full extent of it unfunded pension liability. Portland’s negative position is heavily weighed down by its pay-as-you-go Police and Fire pension program, which causes it to have only a 1% funded ratio. Portland levies an annual capped property tax to cover the pension fund’s current requirements. In the case of Chicago, unfunded pensions are primarily triggering the huge negative position, which is likely to grow even larger under the new accounting rules when the city incorporates them into its books.

Although our research indicates the importance of the net unrestricted position ratio, the rating agencies don’t appear to heavily weight it into the metrics that they base their ratings. As mentioned in Part One of this series on Assessing Credit Quality of America’s Cities, the rating agencies placed about 90% of the 24 largest cities in the AA or AAA category even though very few came close to the 2014 “AA” median for this ratio relative to all cities of 20.6%.

The implementation of GASB’s new Statements 67 and 68 pension reporting standards that will become effective in financial reports over the next couple of years is likely to be a negative driver to the net unrestricted assets to governmental expenditures number. Prior to the new pension rules, governments only reported a portion of their unfunded liability on the statement of net position. With the rule changes, the full amount of the unfunded liability will be included. New York City, which is an early implementer of the new rules, saw its fiscal year 2013 negative unrestricted assets deficit revised from (-128 billion) to (-$193 billion) in 2014, further reinforcing its already negative unrestricted net assets ratio.

The Final Evaluation — Beyond the Bottom Line Numbers

The fiscal challenges faced by cities over the past six years must have felt like a hard punch in the face for many governments that previously tried to keep their head in the sand, so that they wouldn’t have to look straight in the eye at the inevitable back burner realities of pensions, OPEB and infrastructure. As threats of escalating defaults and bankruptcies occupied the press and awakened acute awareness about pensions, America moved in a much needed direction to focus on the vulnerabilities present at the state and local level. Awareness and acknowledgement are always healthy first steps to getting a grip on problems that need resolution.

In hindsight, it shouldn’t surprise many that Detroit, the poster child of this generation’s big city problems, was more than likely to throw in the towel and concede that it couldn’t outlast the gravity of its legacy liabilities in the face of its long-term structural economic decline. For too long there existed a false optimism that the state of Michigan would provide a crutch for Detroit and bear its burdens on a long-term basis without assuming control of its finances. That just wasn’t realistic in a political world in which accountability becomes a legitimate taxpayer issue and dependency reaches a breaking point.

Too often, government officials and politicians have appeased taxpayers by adopting unhealthy fiscal practices by either maintaining expenses they can’t afford or by keeping lower taxes than their liabilities warranted.

By all quantitative numbers, the past few years have seen a gradual comeback for the majority of America’s cities, most of which weren’t weighted down either by heavy debt or other liabilities. Our research into the numbers actually provides evidence that most cities have not only improved their general fund operating and liquidity position above pre-credit crisis levels but have at least temporarily stabilized the erosion relative to its unrestricted net asset bottom line.

Improved pension investment returns and a host of reforms helped prop up pension funding ratios for many cities, but certainly not all. The spotlight on pensions has elevated the world of public pensions to a center stage issue, made them more transparent and somewhat better understood by public officials, investors, rating agencies and even taxpayers. In the past, pension and benefit decisions often received little attention. Back room deals that created down-the-road payoffs are going to be harder to do.

While our research of city pension plans discussed in Part Two of this series found less than 20% of all cities to be in the most fragile critical zone of less than 60% funded, that’s still a substantial problem that is made worse by the fact some of those situations involve major cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, which will place billions of dollars at risk to either taxpayers or investors. Cities with somewhat better funded situations will still require tradeoffs that will require tough choices. A lot of work still needs to be done to protect both retiree benefits and taxpayers in the years to come, especially if there are times of future economic or market crisis that sets back the recent progress. In most cases, the pending GASB pension rules may not have a material impact on taxpayers but they promise to make the reporting more consistent and accurate relative to the total burden.

Besides pensions, there are several other common problems that too often get overlooked. Among them are issues discussed in Part Three of this series:

- Using debt strategies that schedule debt repayment well beyond the a physical project’s useful life risks squeezing out the flexibility to cover future infrastructure needs, especially if the local economy is eroding;

- Not funding other retirement health care funding and

- Deferring repair and replacement of infrastructure.

These situations become much more difficult and expensive to fix the longer it takes to address them. Consequently, they could, if left untreated, jeopardize debt payments, promised benefits and keeping a government from maintaining adequate basic services. At some point, raising taxes alone may only accelerate the downward risk to the economic viability of community whose past appears more glorious than its future.

Taxpayers, rating agencies and investors can help city leaders if they foster and reward cities that maintain not only strong current finances but also those which provide evidence of maintaining prudent long-term practices. Too often, government officials and politicians have appeased taxpayers by adopting unhealthy fiscal practices by either maintaining expenses they can’t afford or by keeping lower taxes than their liabilities warranted. At the same time, investors and rating agencies may be inadvertent enablers if they ignore early signs of imprudent debt policies or other negative credit factors that are developing but not of immediate concern. This laissez-faire attitude may be reflected in borrowing rates or bond ratings that may not take those risks into consideration until the problem escalates to a near-crisis.

There is no single blueprint for identifying all the potential fiscal challenges faced by cities while they are in the making. The appeal of using the unrestricted net assets level created under GASB 34 statement reporting and accompanying ratios as early warning indicators of longer term fiscal condition is that this approach does a reasonable job of providing an early warning indicator that a government is taking on debt beyond its means. While a negative position now might not affect the general fund balance today, it stands to reason that the overall debt-to-asset mismatch found by using the governmental activities financial statement could expose vulnerabilities if deteriorating economic conditions make the burden of government unbearable to future taxpayers.

Finding the right mix of numbers and measures to identify city problems early will help empower stakeholders to better address their problems well before they become a crisis. By the same token, governments doing all the right things to run a tight ship and steer a course within their own means should be rewarded for their good stewardship.

Richard A. Ciccarone is a Co-Publisher of MuniNet Guide. He is also President and Chief Executive Officer of Merritt Research Services, a municipal bond credit database and research company that primarily serves institutional investors, investment dealers and bankers. Mr. Ciccarone has over 35 years of investment management and research experience, specializing in municipal bonds.

Did you see the earlier installments of this series?

Part One: Focusing on Bond Ratings

Part Two: The Achilles Heel to the Fiscal Condition of Cities – Public Pensions

Part Three: Long-Term Liabilities Beyond Pensions

Part Four: FY 2014 Financial Condition